2 Media Hot and Cold

This week in this series looking at 'Understanding Media', we dive into maybe the most confusing area of McLuhan media studies: Hot and Cool media.

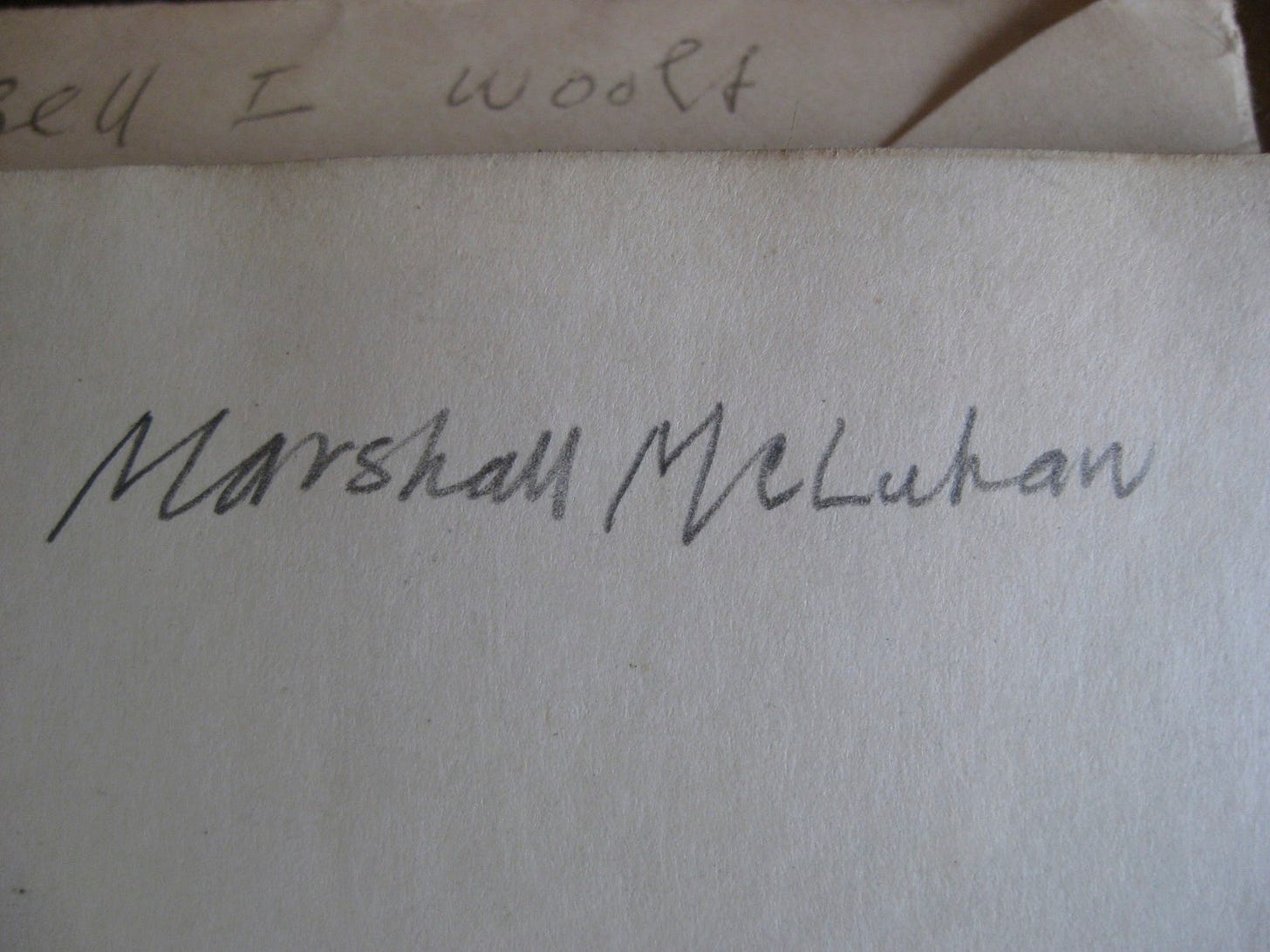

Hot and Cool have caused trouble since day one, and the trouble persists. It famously caused Alvy Singer to bring Marshall McLuhan into the picture to tell the hapless Columbia prof “you know nothing of my work.” Horton, who played the put-upon professor remarkably maintained character integrity for many decades after the film, continuing to mistake the message. (Horton is on the record with one version of the circumstances around the filming of that iconic scene — I heard another, somewhat different story — for another time.)

TLDR: Hot and Cool are relative to each other, technical terms to describe the relative high or low definition or amount of data or information being delivered to a user, and the corresponding reaction from the user. Higher definition or stimulation, lower response from the user. A lower amount of definition, or information, or stimulation, requires more from the user to complete the meaning.

Shorter: “…the effect of a medium is in what it omits and what we supply.” (McLuhan to Muller-Thym, 1960)

In this series, we are examining the first part of Marshall McLuhan’s ‘Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man’ chapter by chapter, looking at each chapter as comprising a distinct method of examining the nature and effects of technology, of human innovation.

In the first chapter, ‘The Medium is the Message,’ we looked at media as environments. In this review of the second chapter, we look at media as instruments, their nature and effects.

Maybe the first thing to notice about ‘hot and cold’ is that they are relative terms. Whether anything is hot or cold depends on your point of view, the same way whether a dish is spicy or not depends on your tolerance. So, whether a medium is hot or not can depend on the context (environment) and the user.

“…since no medium has its meaning or existence alone, but only in constant interplay with other media.” (p.26)

The second paragraph of the chapter in question lays out fairly completely, if complexly what are meant by the terms hot and cool:

“There is a basic principle that distinguishes a hot medium like radio from a cool one like the telephone, or a hot medium like the movie from a cool one like TV. A hot medium Is one that extends one single sense in ‘high definition.’ High definition is the state of being well-filled with data. A photograph is, visually, ‘high definition.’ A cartoon is ‘low definition,’ simply because very little visual information is provided. Telephone is a cool medium, or one of low definition, because the ear is given a meagre amount of information. And speech is a cool medium of low definition, because so little is given and so much has to be filled in by the listener. On the other hand, hot media do not leave so much to be filled in or completed by the audience. Hot media are, therefore low in participation, and cool media are high in participation or completion by the audience. Naturally, therefore, a hot medium like radio has very different effects on the user from a cool medium like the telephone.” (p. 22)

That’s a hot paragraph. Maybe too hot for many. One way to cool it down it to break it down, dilute it with space, dissipate the heat. Take it a piece at a time rather than shove the whole thing in your mind at once.

“There is a basic principle that distinguishes a hot medium like radio from a cool one like the telephone, or a hot medium like the movie from a cool one like TV.

A hot medium Is one that extends one single sense in ‘high definition.’ High definition is the state of being well-filled with data. A photograph is, visually, ‘high definition.’

A cartoon is ‘low definition,’ simply because very little visual information is provided.

Telephone is a cool medium, or one of low definition, because the ear is given a meagre amount of information. And speech is a cool medium of low definition, because so little is given and so much has to be filled in by the listener.

On the other hand, hot media do not leave so much to be filled in or completed by the audience.

Hot media are, therefore low in participation, and cool media are high in participation or completion by the audience.

Naturally, therefore, a hot medium like radio has very different effects on the user from a cool medium like the telephone.”

These are comments on the nature or makeup of a technology being more or less filled with data or information (heat), and the effect of that on a user: that the more information or date we are given, the less we have to do. It is a study of the mechanics of human-media interaction. Stimulus and response.

He uses the example of photograph contrasted with cartoon. With a photograph (assuming a clear image) we are given a high definition image, compared to a cartoon or simple drawing. We fill in a lot of blanks to ‘make sense’ of the cartoon image. We might say that with a cartoon ‘much is left to the imagination.’

Again, the goal of the book is ‘understanding media’ and here we are given criteria to evaluate the nature of one category of technology (extensions of our senses), and their effect on the user.

McLuhan addressed the trouble with hot and cool in the preface to the third printing of Understanding Media in 1966 (I believe) when he wrote:

“The section on ‘media hot and cool’ confused many reviewers of Understanding Media who were unable to recognize the very large structural changes in human outlook that are occurring today.” (p. vi)

It seems slightly to the side of this discussion of hot and cool, but he continues:

“Slang offers an immediate index to changing perception. Slang is based not on theories but on immediate experience. The student of media will not only value slang as a guide to changing perception, but he will also study media as bringing about new perceptual habits.” (p. vi)

Language is among our oldest technologies, yet remain current because they change as we do. Put against a smartphone which becomes an expensive paperweight in a few short years, it’s remarkable how under-celebrated languages are.

True to ‘the medium is the message,’ McLuhan is here drawing attention to the value of the form of language over its content. Language is one way we express our experience, the means by which we grapple with experience and give it form, express or put it outside ourselves. It is useful to note that language changes in reaction to something. Something has changed to cause language to change to meet the difference. It may not always be clear just what the change means, but it’s something to mark it.

For example, I’ve notice an expression has become very common: “I feel like…”

I feel like there’s been a change lately in how we express some things.

I feel like we don’t tend notice these kinds of changes, much less attach any significance to them.

“Early in 1960 [see the letter to Bernard Muller-Thym, below] it dawned on me that the sensory impression proffered by a medium like movie or radio, was not the sensory effect obtained. Radio, for example, has an intense visual effect on listeners. But then there is the telephone which also proffers an auditory impression, but has no visual effect. In the same way television is watched but has a very different effect from movies. These observations led to a series of studies of the media, and to the discovery of basic laws concerning the sensory effects of various media. These will be found in this report.”

--Marshall McLuhan ‘General Introduction to the Languages and Grammars of the Media’ 1960.

Dated June 30, 1960, ‘Report on the Project in Understanding New Media’ is the 136-page document you’ve never heard of, which would become the 1964 guidebook ‘Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man’ you have, presumably, heard of.

The Report is the product of a year or so of focused study of the nature of human innovation and their individual and social effects, a study funded by the National Association of Educational Broadcasters (NAEB), and the study which I believe was a turning point for Marshall McLuhan in not only his understanding of the nature and effects of human innovation but also his understanding of how much agency we humans have in determining what those effects will be.

I pointed this change out in part two of Maelstrom Escape Strategies:

“Improvements in the means of communication are usually based on a shift from one sense to another and this involved a rapid refocusing in all previous experience. It is, therefore, a simple maxim of communication study that any change in the means of communication will produce a revolutionary consequences at every level of culture and politics. And because of the complexity of the components of this process, prediction and control are not possible.” ('A Historical Approach to the Media’, 1955)

And a few years later, quite the opposite view:

“Communication, creativity and growth occur together or they do not occur at all. New technology creating new basic assumptions at all levels for all enterprises is wholly destructive if new objectives are not orchestrated with the new technological motifs.

…All of my recommendations, therefore, can be reduced to this one: study the modes of the media in order to hoick all assumptions out of the subliminal, non-verbal realm for scrutiny and for prediction and control of human purposes.” (Report, 1960)

Said another way:

“Recognition of the psychic and social consequences of technology makes it possible to neutralize the effects of innovation.” (letter to Life Magazine, 1966)

More simply:

“There is absolutely no inevitability as long as we are willing to contemplate the situation.” (‘The Medium is the Massage,’ 1967)

I find that change of opinion endlessly fascinating. What happened to change his mind was his intense study of the media in preparing the 1960 NAEB report. While the Report doesn’t seem to have made much of an impact, the study leading to it was pivotal for McLuhan, and he acknowledges as much on the copyright page of the early editions of Understanding Media:

“Special acknowledgements are due to the National Association of Educational Broadcasters and the U.S. Office of Education, who in 1959-1960 provided liberal aid to enable the author to pursue research in the media of communication.”

SI/SC – sensory impact, subjective completion

I could have, maybe should have, led off this essay/article/thing with the following. A few months before the date on the report, McLuhan sent this exited letter to his friend, Bernard Muller-Thym:

"The breakthrough in media study has come at last and can be stated as the principle of complementarity: that the structural impact of any situation is subjectively completed as to the cycle of the senses.

That the effect of a medium is in what it omits and what we supply, but the factors of high or low definition image may qualify this radically.

That in telephoning, for example, we are dealing with such a low definition auditory image that we are engaged in completing that rather than filling in the visual, etc.

Low definition, on the other hand is the basic principle of organized ignorance, and of the technique of invention."

The letter is quoted in Terrence Gordon’s biography of Marshall McLuhan, and is not in the ‘Letters of Marshall McLuhan’ collection but at Libraries and Archives Canada in Ottawa, which houses the other 90% of the letters which have not been published.

The key piece in this letter is the uncomfortable “as to the cycle of the senses.” Not for the first time, nor for the last, will I have to bring up that for McLuhan, it all comes down to our senses.

Our senses are our interface between the exterior world and our selves. The quality, the nature of our experiences, are informed by the quality, the nature of our senses individually (each sense on its own and how it’s calibrated) and collectively (all our senses together as they form our awareness, as they form us.)

Additionally, our senses are not static things but they change – and when they change, we change. To affect or change one sense affects and changes all the senses because they exist with a balance or equilibrium between them. If you shut off sight, or any other sense, the rest of the senses adjust. That adjustment changes many things about us, who we are, our identities – and as a group, our societies, cultures.

We are the sum of our senses.

When McLuhan is talking about ‘participation’ and ‘involvement’ he is often talking about our senses and how they react to stimulus.

When he says ‘extends one single sense in high definition’ he is referring to the title of the book, that his definition of media is that they are extensions, amplifications, artificial constructions of some part of us – in this case, our senses.

As typical with Marshall’s method in the book, he states variations of the same thing over the course of the chapter as he tries to get an idea across, ranging from technical and complex (as above) to simple:

“…the hot form excludes, and the cool one includes.” (p.23)

A simple way to illustrate how ‘cool’ or low information/definition includes or demands participation to ‘complete’ is whispering: our senses strain. When someone speaks at low volume you might lean in, cup your ear, maybe even close your eyes to focus your attention. On the opposite end, if something it too loud of too bright, you might shield or close your eyes, cover your ears.

I have not nearly exhausted the topic, but cherry-picked a few things to draw out a little further in trying to get out the basic concept of hot and cool in a way that might help you not only understand it but use it.

Thanks for reading.

Next week we’ll be back with Chapter 3 - Reversal of the Overheated Medium

Take care,

Andrew McLuhan

references: page numbers are from the fifth printing of Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man.’

I contemplate ongoing what temperature the internet is. It is usually high definition in multiple senses at once. TV the 50s and 60s was a cool medium due to the scan lines and shitty speaker on the side of the box (to which my dad taped a microphone to record the news doing his Ph.D. work at NYU). In U.M. I recall Marshall saying that "high definition TV would be a whole other thing." The internet is loaded with high def video combined with high def audio. Plus you touch the thing, and talk to it. So how would you start to work out this question, or are we beyond the hot/cool binary in addressing total digital conditions?