In ‘The Medium is the Message’ (chapter 1) we learned to look to the environment. In ‘Media Hot and Cold (chapter 2), that the level of definition, stimulus, data in a medium (artefact) is related to the user’s reaction, involvement, participation – the user’s experience. Now we are warned that any medium (environment) is a dynamic process with a point of no return.

Marshall McLuhan was interested in the nature of, and the individual and social effects of technologies. What they are, what they do; the two things being closely, inextricably, related. ‘It is what it does’ is one way of rephrasing ‘the medium is the message.’

To repeat what I’ve said earlier in this series, ‘Understanding Media’ is a guidebook with a two-part structure. In ‘Part One’ of the book, Marshall McLuhan lays out what I think of as general principles of technology, things common to all human innovation and artefact. Constants in the nature and effect of the things we make and do. In ‘Part Two’ he takes these general principles and applies them to specific things from The Spoken Word (chapter 8) to Automation (chapter 33).

None of these general principles can tell you everything about anything, but each of them is a piece of the puzzle that when put together can add up to a revealing picture. The point being to ‘understand media.’ And, when you’re trying to understand what something is and what it does, if you’re the rare person who ever attempts such things, the more starting points the better. Often, even a point of disagreement can be a fruitful one.

Why anyone should want to study media at all is another interesting question for another time. One interesting aspect of that question is that whenever I ask it, almost all of the responses are jokes. Few joke when you ask why we should study the (natural) environment, or the human body (another kind of environment.) Many reasons for studying them are common to all three.

Another thing I have commented on elsewhere, though not yet in this series, is that people seem to skip over a vital step when it comes to looking at what a technology is and what it does – which is what ‘media studies’ (at least in the McLuhan tradition) are concerned with. That vital step is to first establish what a medium is, what media are. What is a medium? What are media?

(Like ‘why study media,’ many meet the question ‘what is a medium’ with a jokey answer.)

The title of the book gives you Marshall McLuhan’s basic definition: media are ‘extensions of man,’ ‘any extension of ourselves in material form.’

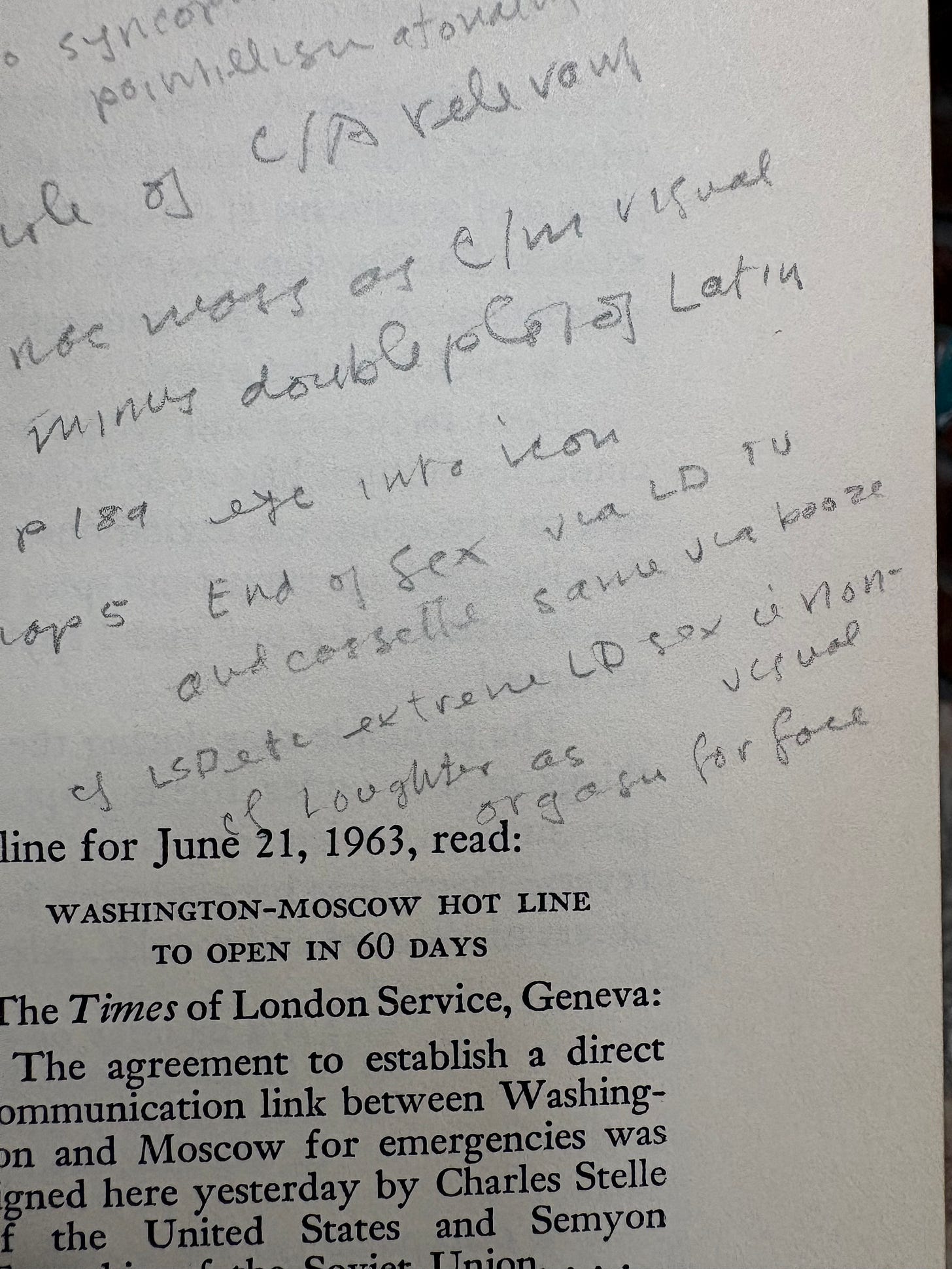

And of course, the ‘message’ of any technology is ‘the change of scale or pace or pattern that it introduces into human affairs’ (p.8) ‘because it is the medium that shapes and controls the scale and form of human association and action.’ (p.9*) (*I’m quoting, and photos here are from a first edition of Understanding Media. Page numbers will differ in later editions.)

Marshall McLuhan tended to speak of media in two ways: as instruments or artefacts (things), and as environments, and you do have to pay attention to figure out which is being referred to at any time.

“To say that any technology or extension of man creates a new environment is a much better way of saying the medium is the message. Moreover this environment is always invisible and its content is always the old technology.” (letter to Buckminster Fuller, September 1964)

For those uncomfortable with the collective noun ‘man,’ he also in 1966 said that any medium is ‘an extension of human powers.’

So a medium is a human innovation which enhances, amplifies, extends some human sense or function, as a cup amplifies our ability to drink water or liquid; a telephone, our ability to speak with someone. In turn, this creates a new medium or new human environment for us with new ‘services and disservices’ or affordances and consequences. It makes some things possible, and tends to make other things untenable. Fast internet and video calls makes work from home possible but in the process changes both work and home. They are different worlds, different environments – different media. A new medium is a new culture and often incompatible with the old one. Crucially, we never seem to take this into account with creating or adopting new technologies, we never seem to think of the effect of the new medium on the old before it’s too late, we’re just preoccupied with what the new medium can do for us rather than what it will do to us.

So people get off on the wrong foot by not even considering in the first place this word ‘medium.’ Then they may get a little confused about whether we’re talking about an instrument (medium) or an environment (medium). The truth is, human technologies are both things – instruments which modify and create environments, which modify and (re-)create us.

“any technology gradually creates a totally new human environment. Environments are not passive wrappings but active processes.” (p. vi)

That last one is a key bit. Active processes. Like us. We are not fixed but change. Like water, we take on the shape of our container, our media. As that container changes, we change. It seems this is a never-ending process of invention and change where we shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us, causing us to shape more tools, reshaping us again, over and over since time immemorial.

Both we, and our media, are active processes.

Speaking of active processes, back to the particular subject at hand, reversal:

“The principle that during the stages of their development all things appear under forms opposite to those that they finally present is an ancient doctrine.”

(p. 34)

“The present chapter is concerned in showing that in any medium or structure is what Kenneth Boulding calls a ‘break boundary’ at which the system suddenly changes into another or passes some sort of point of no return in its dynamic processes.”

(p. 38)

Another Canadian, Malcolm Gladwell, later referred to this point of no return a ‘tipping point.’

Marshall McLuhan pointed out many reversals in his and our time. One, which makes me laugh on an almost daily basis, is the change ‘from jobs to roles’ which he pointed out over half a century ago. Today you can’t avoid people now referring to their ‘role’ or ‘looking for a new role,’ ‘hiring for a new role,’ etc.

The key insight of this chapter is that in any process there comes a point in which things tend to change, often in a dramatic reversal.

This principle of reversal is also one of the four ‘laws of media’ which were discovered or developed by Marshall and Eric McLuhan in the early 1970s. These four ‘laws’ could be illustrated graphically, and that is known as the ‘tetrad.’ (A tetrad is a group of four things).

I remember several years ago my father was invited, through an inside connection (shoutout Scott) to give a workshop on tetrads/laws of media at Facebook in Menlo Park, California. I don’t think it went very well really, and I actually suspect dad didn’t try too hard to make a good impression because he wasn’t really interested in teaching this kind of stuff to those kinds of people – why teach them to be better at what they do and make things worse than they already are? That’s just my hot take on it.

Explaining the ‘reversal’ quadrant at the start of the workshop, dad talked about alcohol like this: ‘If you’re drinking a bottle of wine at a dinner party, one glass, two glasses, makes things bright and fun. Three glasses, maybe starting to get a little wild. Four glasses, five glasses, you’re starting to make a fool of yourself, seven glasses you’re in the bathroom vomiting and after that you wake up in a bad state the next day wondering what happened.’

“The stepping up of speed from the mechanical to the instant electric form reverses explosion to implosion. In our present electric age the imploding or contracting energies of our world now clash with the old expansionist and traditional form of organization. Until recently, our institutions and arrangements, social, political, and economic, had shared a one-way pattern.” (p.35)

If ‘Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man’ has a setting, and I treat it that way, it is at the point of switchover between two great eras, the mechanical and the electric. The scene is set (pretty dramatically) as the Introduction opens:

“After three thousand years or explosion, by means of fragmentary and mechanical technologies, the Western world is imploding. During the mechanical ages we had extended our bodies into space. Today, after more than a century of electric technology, we have extended our central nervous system itself in a global embrace, abolishing both space and time as far as our planet is concerned. Rapidly, we approach the final phases of the extensions of man—the technological simulation of consciousness, when the creative process of knowing will be collectively and corporately extended to the whole of human society, much as we have already extended our senses and nerves by the various media.”

In 1964 that sounded pretty far out. Today, it sounds like… today. The paragraph continues but if I keep going I’ll never get this article done, an article already perhaps past the point of no return from being a brief summary to a long-winded meditation.

Here’s maybe a good place to land this for now:

“One of the most common causes of breaks in any system is the cross-fertilization with another system, such as happened to print with the steam press, or with radio and movies (that yielded the talkies). Today, with micro-film and micro-cards, not to mention electric memories, the printed word assumes again much of the handicraft character of a manuscript.” (p.39)

Conservatives and puritans across the ages have believed, with varying results, that to keep it whole, you have to keep it pure. Of course, stagnation is another common cause of break in many systems.

Ecology is a delicate thing.

One question I’m left with, as regards tipping points and reversal, and ecology, is that if we know that any structure has a point in which “the system suddenly changes into another or passes some sort of point of no return in its dynamic processes,” how might we monitor in order to avoid passing it? How might we anticipate it? This, to me, would be actual rather than fanciful ‘responsible tech.’

As we near the end of the year, thank you for being on this journey with me. I appreciate the support of your attention and subscription. I’ll try to get one more of this series done before eoy.

If you want to dive deep into this work with me and a group starting January 7, check out Understanding Media Intensive, a course I lead through Gray Area.

Two thoughts.

1. For a long time, we have treated media as a thing. As a result, we do not understand it in its fullness. We only see it as a means of exploitation. Look at the criticisms about social media and smart phones. They are treated as objects for criticism and disgust. What is missing is the realization that these forms of media are environments that we live in. The experience has real effects that cannot be objectified. People are changed. Society is changed by the creation of these digital environments. This change goes beyond the material confines of the objects that constitute media. It represents a reversal of historic proportions.

2. In many respects, the reversal we are witnessing is the throwing over of Enlightenment rationalism for something whole and embodied. The reductive nature of objectifying every aspect of human existence ends up turning us into objects as well. However, as I am seeing in my interactions with people, they are rejecting the the cold, hardness of language as a thing. Instead, they are looking for something more, something whole. The best illustration that I have of this is music. The score is the medium of thought. The performance is the medium of living. I've discovered this as I joined the choir at my church. This Sunday we are singing a Mendelsohn cantata. It is so hard to move from the words and notes on the page to the wholeness of the performance. It is transformative. It has helped me see the interplay of the two mediums that Marshall and you describe.

Iain McGilchrist has addressed this in his description of the asymmetical hemispheric relationship between the left and right brain. The right brain of intuition and experience sees a world that is whole. The left brain sees a world as a collection of things, objects. The Enlightenment process objectifies things. Everything is a thing. As a result, we are detached from the experience of the thing. The reversal that I see here is the growing importance of experience as a source of knowledge. The medium of human experience is the medium of life. Your grandfather and father gave us the metaphors for seeing this. Thank you for bringing this to us in a form that we can access and make sense of.

Thanks for this very enjoyable post. One of the key points I think is this: "Marshall McLuhan tended to speak of media in two ways: as instruments or artefacts (things), and as environments."

And along with that another key point: McLuhan pointed out that media environments are always invisible.

Indeed, he often referred to the saying: "We don't know who discovered water, but we know it wasn't a fish."

Our tendency to see media as instruments or tools prevents us from recognizing their pervasive (and invasive) environmental effects.

You convey this idea well when you write: "we’re just preoccupied with what the new medium can do for us rather than what it will do to us."

And of course, Marshall wrote about the numbing effects of these environments in his Understanding Media chapter entitled: "The Gadget Lover: Narcissus as Narcosis" (pp. 63-70 in the Gingko edition).

In his 1984 book, "Technology and the Canadian Mind," Arthur Kroker writes:

"McLuhan's project was to break the spell cast upon the human mind by electronic technologies --- radio, television, computers, video games --- which operate in the language of seduction and power...He was therapist to a population mesmerized, and thus, paralyzed, by the charisma of technology."