Against Inevitability, Toward 'Psychological Decentralization.'

Marshall McLuhan died this day, New Year’s Eve, 1980. For the last year of his life (and a bit) he was unable to communicate very much: some thoughts on befores and afters.

While often noted for the irony of it, I consider irony to be the least interesting aspect of Marshall’s stroke and loss of speech.

As it happened on such a prominent date, my grandfather’s death and the end/beginning of the year are inextricable for me. I probably spend more time than most people do thinking about a grandparent, given that I am in one way or another involved with his life and work on an almost daily basis – from adding content to The McLuhan Institute’s Twitter account to deep reading and research of his and my father’s works, speeches, books.

It’s also natural at this time to think about lesser and greater forms of death and birth: the passing and beginning of one year to another, of ages, eras, of generations both human and technological, if that remains a practical distinction. So here we are.

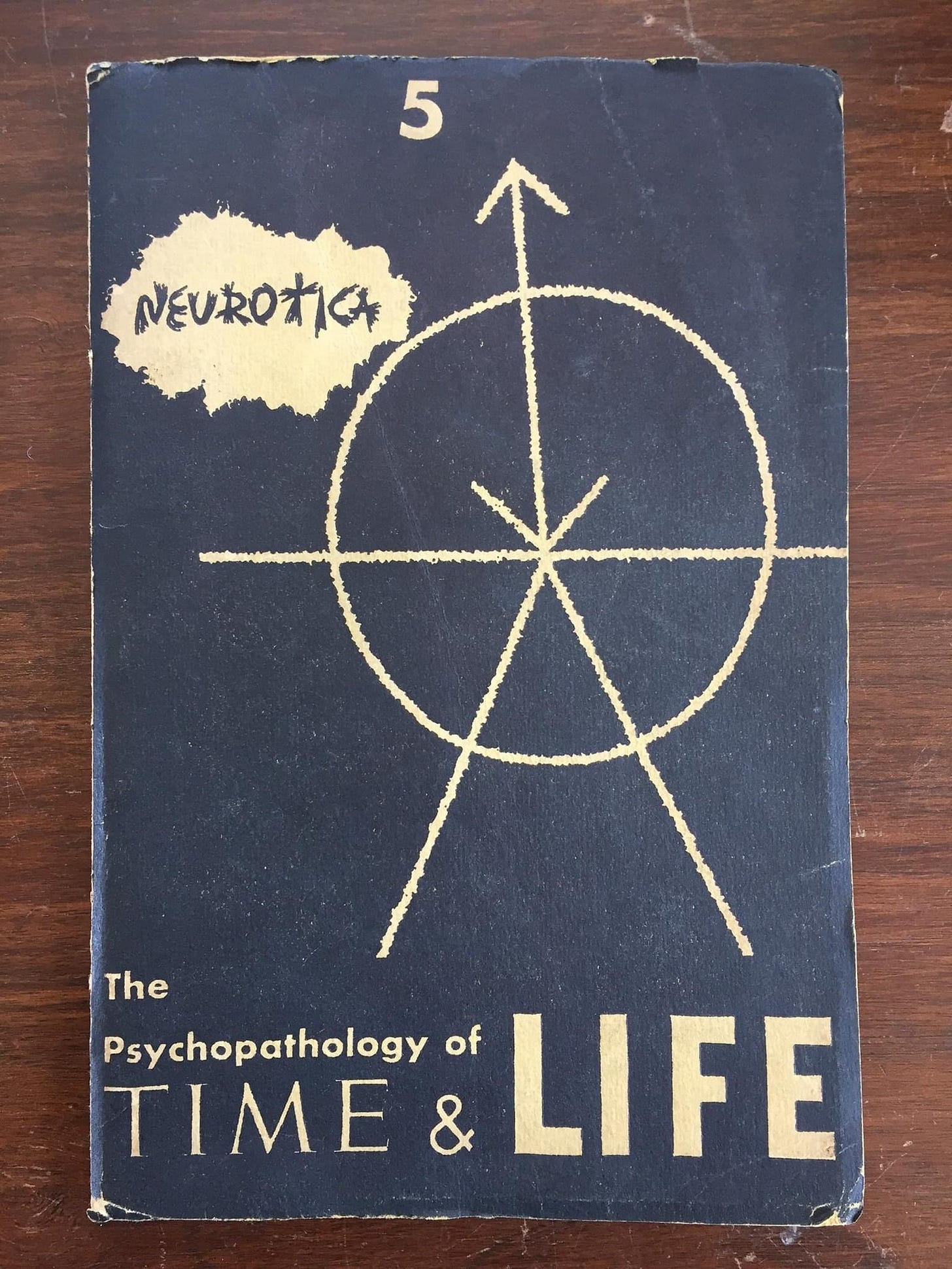

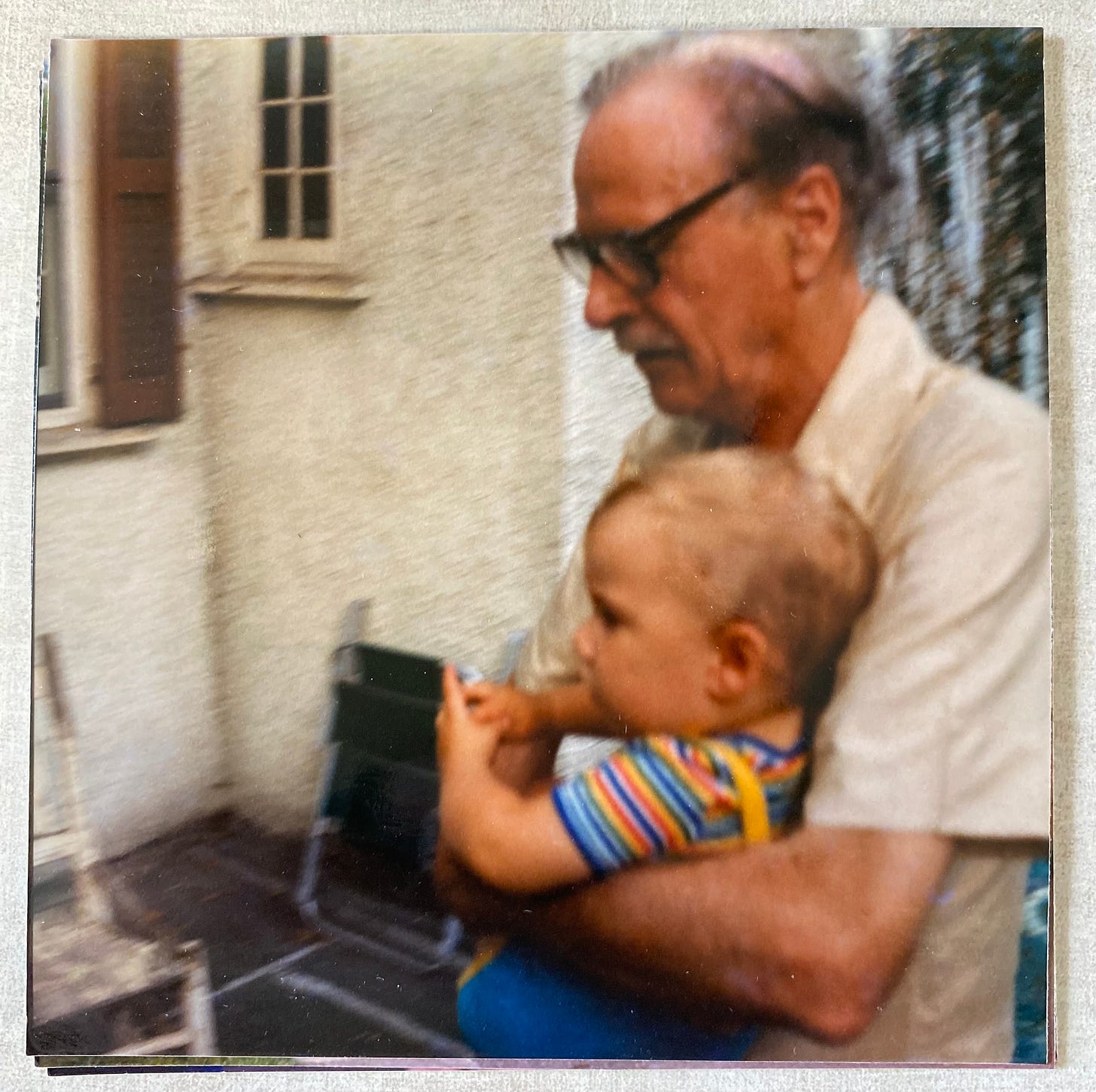

In the fall of 1979, when I was just over a year old, Marshall suffered a stroke (neither his first nor last) which removed from him his ability to communicate in the manner to which he was accustomed: frequently, forcefully, eloquently. From then on he would only be able to make himself understood in the most basic way. Gestures, noises. Frustrations. What a fall. What torture for someone who was not only accustomed to expressing so much so frequently, but had such a need to express from a mind never at rest. To be suddenly cut off from all but the most basic of communication would be a particular horror, torture. It’s maybe easier for us to imagine today when we are paired with devices which we constantly and compulsively monitor and broadcast. Take a moment to think about what it would mean to cut that off completely right now. It would be a shock and require quite an adjustment. That brings to mind something Marshall wrote along these lines in a very little-known essay published in a very little-known journal ‘Neurotica’ in 1955 [edit: 1949]:

“The process of renewal can’t come from above. It can only take the form of reawakened critical faculties. The untrancing of millions of individuals by millions of individual acts of the will. Psychological decentralization. A merely provisional image of how it might (not how it should) occur could be formed by supposing every mechanical agency of communication in the world to be suspended for six months. No press. No radio. No movies. [No smartphones. No Internet.] Just people finding out who lived near them. Forming small communities within big cities. It would be agony. All psychological drugs cut off. No capsulated thoughts or melodies. To say that anything like this could never happen, or that it should never be allowed to happen, is a remark worthy of those mesmerized practical men who are efficiently arranging for the obsequies of our world’s mind and body alike. If something like this doesn’t happen it is quite plain what will happen.”

Today, six months of that would not only ‘be agony,’ it would be such chaos it’s hard to imagine the world recovering the situation which was collapsed.

‘The Psychopathology of Time and Life’ is a remarkable essay falling at the point where Marshall McLuhan is turning from a career in teaching poetry and literature to a career in studying media and becoming a kind of ‘anti-environmental activist’ in terms of the invisible shaping environment which is what hides the effects of technologies from us, actively reshaping us and our families and societies as we are ever-increasingly absorbed in their content, the creation and consumption thereof. It reflects a younger Marshall McLuhan, less careful to avoid strong opinions, a style very different from what readers of ‘Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man’ (1964) would expect.

To wake from a stroke with circumstances so starkly altered would have been a shock for anyone, a special torture for Marshall McLuhan. Though Marshall had largely fallen from the world’s attention after the 60s he had hardly stopped working. In fact, being freed from public demand afforded him the opportunity to spend more time working. My father Eric McLuhan was at his side all this time and together they did some remarkable work, notably discovering and developing the four ‘laws of media.’ They discovered that all human technologies, as extensions of ourselves, have four things in common: they ‘enhance’ or amplify some sense or ability or function, they ‘obsolesce’ or take over from or push aside another innovation and generally take it as content, they ‘retrieve’ or bring back in a new form something from the past, some previously-obsolesced innovation, and when pushed to an extreme, the new form flips or ‘reverses’ into something else.

Marshall and Eric discovered that all human innovation behaves according to these laws. That while all technologies might do many different and unique things, that they all enhance/obsolesce/reverse/retrieve in this manner. This is a pretty big deal, as big a deal as the discover of the laws of physics or thermodynamics or gravity, though much lesser-known.

Marshall and Eric were working on this, among other things, when Marshall had that stroke. Work was paused, expected to resume. Marshall was 68 years old.

68. It’s kind of incredible to think he was that young.

Work on the ‘Laws of Media’ was not the only thing that was paused: Marshall’s career was paused.

Marshall was still a full-time professor at the University of Toronto, in St. Michael’s College’s English Department. He was still director of the Centre for Culture and Technology. But his position was not what it was. No longer sought out as frequently by the media he criticized, his classes had very low enrollment. He no longer had the support on campus he had enjoyed in the 60s with then-present Claude Bissell at the helm of UofT (1958-1971).

With Marshall’s stroke making him unfit for teaching, he was forced into retirement. The Centre for Culture and Technology, once attracting visits from dignitaries such as Prime Ministers and John Lennon and Yoko Ono, was closed, shuttered, used for storage. A brief campaign was mounted to keep it open, with letters of support from prominent people, but it was claimed the building was needed for storage and it was shut.

The Centre for Culture and Technology reopened a few years later, in the early 80s but it wasn’t the same. Marshall had left the building both literally and certainly at this point spiritually. Little to nothing remains there today of him or the work he begun. There’s a story here I’m glossing over. It’s a story of jealousies and politics, academic and otherwise. My father, to me the person who should have perhaps at some point directed the Centre, never had the opportunity. And for my part, being privy to all the events at a bit of a remove, if also intimately, it makes me glad I didn’t seriously try to get involved. I wasn’t interested in university when I was of an age to go, and having seen what happens (and doesn’t happen) in academia, I’m glad I chose to study on my own and start The McLuhan Institute as an independent organization.

As a teenager, finding this stuff out, it really pissed me off. But I digress.

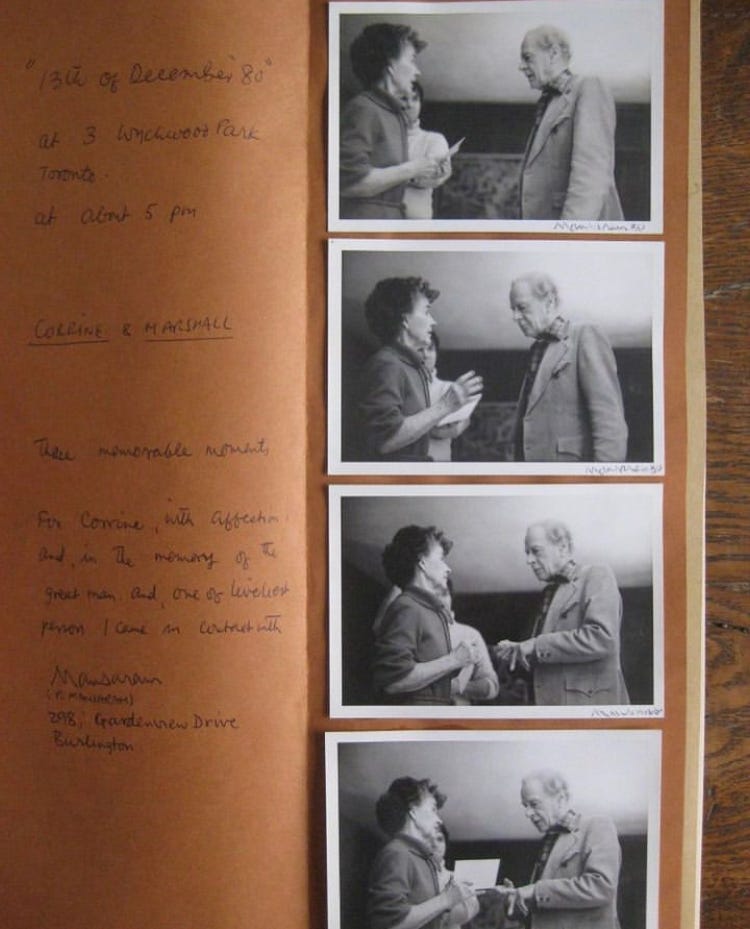

Fr. Francis Stroud wrote a lovely account. One of the last people to spend any time with Marshall McLuhan, he happened to spend much of Marshall’s last few days on earth with him at home:

“Almost a year and one-half ago Marshall had had a stroke, and although he was almost completely recovered physically and certainly mentally, the tragic irony was that this most eloquent communicator on communications was rendered speechless. He was undergoing therapy to regain his speech, but it was such a frustration to him that he would rarely see even close friends for more than a short time. It was just as much a disappointment to his many friends and admirers. Pierre Trudeau, the Prime Minister, would frequently call in to visit and discuss anything from culture to matters of state. When Marshall would visit his daughter in California, Governor Brown would have a limousine meet him at the airport so he could snatch a few hours of personal conversation with Marshall. … There was so much insight, so much stimulation, so much enjoyment. Marshall loved a good laugh. In a brief, simple homily during the last mass of his life, he heartily laughed at a joke I told him of Jesus’ hidden life. John Culkin, during his warm and moving eulogy at Marshall’s funeral mass, eloquently touched on this wonderful trait when he said that Marshall was the kind of person who knew that ‘manslaughter and man’s laughter were spelled the same.’ It all depends on where you put the emphasis. … The next day, Tuesday, we did the same thing: Mass [Fr. Stroud had said mass for Marshall at the McLuhan home], walks, readings. I bought a couple of bottles of champagne which we used to toast him and our get together before dinner at home that night. He took me to his den so we could watch the 11 o’clock news together. I promised him I would see him in the morning before I left. That night, he died peacefully in his sleep.”

--J. Francis Stroud, S.J., ‘The Jesuit Connection and Marshall McLuhan.’ 1980

I was a less than two years old. I couldn’t speak much, either. I’m told that we used to have babbling, nonsense conversations between us – at least, that’s what it sounded like to everyone else. I think it made sense to us at the time, and I like to think that it meant a lot to both of us too.

The thing is, as Culkin mentioned through Stroud, Marshall had this vitality. As much as this was an awful situation, Marshall was not one to dwell or let something like that get him down. He had the example of Jacques Lusseyran to follow. Jacques didn’t let his loss of vision keep him down, and neither did Marshall let his loss of communication.

My suggestion is that, relieved of the ability to communication, Marshall was relieved of the responsibility. With his mind constantly churning over ideas, he spent decades feverishly working and expressing them. At great cost. Now, unable to express, maybe even explore those things, he had to find what joy he could from life and that was in friends and family.

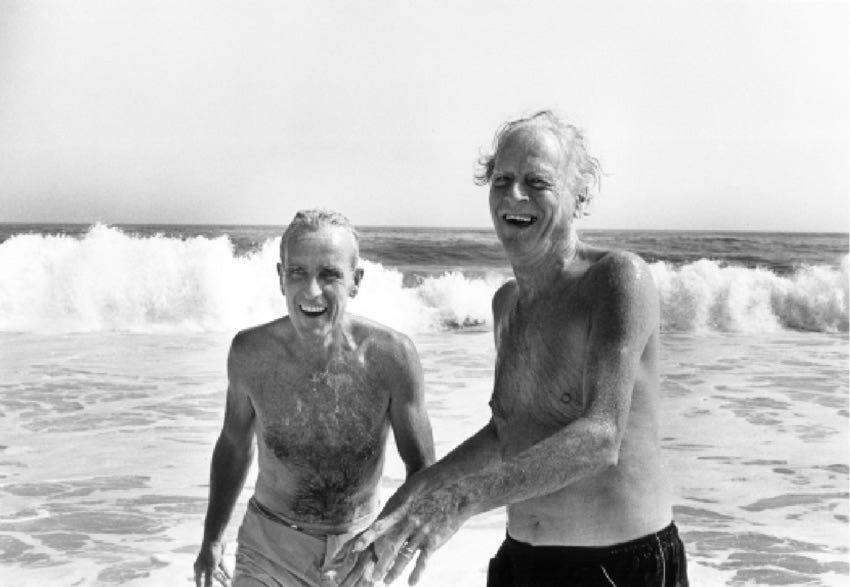

I see some family photos where Marshall obviously looks aged and frustrated. But I see other photos where he’s the happiest I’ve ever seen him – the photos from his visit to the Carpenters on Long Island are a striking example.

On this night – New Year’s Eve 2023/2024 – when it seems we’re not only stepping into a new year but into a new world with AI swallowing us at a frightening pace, I am sitting at my kitchen table, the dog at my feet. My wife and our boys are in the den and I’ve promised to finish this by dinner to spend the rest of the evening with them.

I’m thinking of what’s behind, what’s ahead. What’s happened, what could happen. What I can do, what I should do.

For my part, I believe that the work my grandfather started all those years ago, that my father kept going in his own way, that I’ve stepped into now as well – I believe that work is as vital as ever, and more needed than ever. Technological change comes fast and furious and we’re getting to the point where we could drop off the precipice and drown in the vortex which has a grip on us as mighty as it is uncredited. We seem unwilling to see it for what it is, the people in charge in industry or in government seem unwilling to do anything about it, and it’s easy to despair.

But I know that my grandfather lived and worked in hope and faith. Faith that we were not as helpless as we assumed. Hope that we would eventually figure it out and do something about it.

“There is absolutely no inevitability as long as there is a willingness to contemplate the situation.”

-Marshall McLuhan ‘The Medium is the Massage’ 1968.

“Our concern is to explore and reveal the process patterns of current happenings. Since it is no longer safe to wait for the harsh judgement of results, we must discover how to anticipate effects with their causes in order to avoid the ‘inevitable’ by ‘programming fate.’”

Marshall McLuhan and Barrington Nevitt

’Take Today: The Executive as Dropout’, 1972

Thank you for your support of this first year of The McLuhan Newsletter. All the best to you and yours from me and mine for the new year.

-Andrew McLuhan