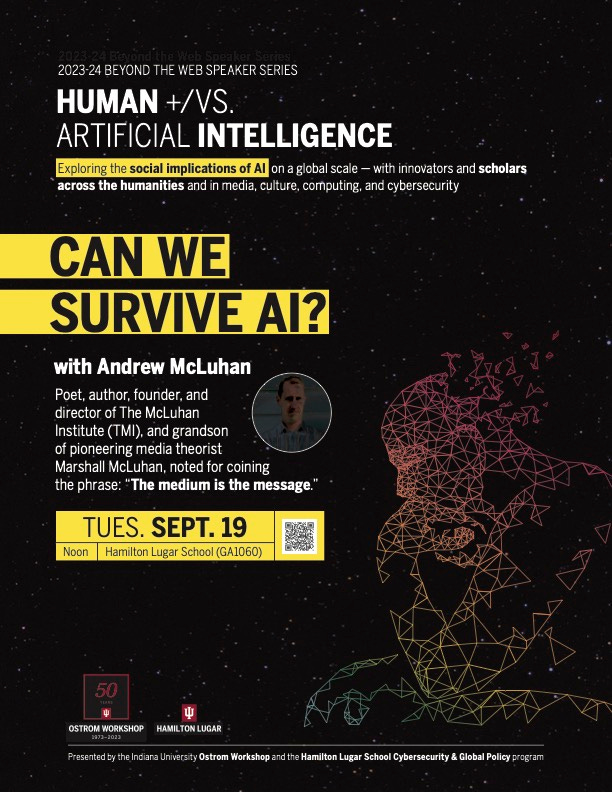

The following is part one of the text of a talk given at the University of Indiana, Bloomington, on September 19, 2023. I pose, then consider a few different sides of this question. Thanks due to Doc and Joyce, Isak, the Hamilton Lugar School and Ostrom Workshop, for the opportunity to present these remarks. Keep and eye on their ‘Beyond the Web Speaker Series’ for upcoming guests speaking to similar topics.

Considering this question, I first answered ‘yes and no.’

Yes, we can: Ours is a history of developing technologies which revolutionize our ways, changing who we are and what it means to be human – and that might just be the definition of what it means to be human.

No, we can’t: AI is poised to revolutionize the way we do many things, which will existentially change who we are and what it means to be human

Yes, we will survive; no, we will never be the same.

The bad news first: we can’t survive AI.

But the bad news isn’t as bad as it might sound. We tend to get alarmed about things which aren’t all that alarming, and tend to ignore many things which should alarm us. That seems to be a very human trait.

What shouldn’t alarm us is that AI is going to change many things about who we are at fundamental levels as individuals, as groups. This shouldn’t alarm us because this is not really anything new.

What should alarm us is that AI is going to change many things about who we are at fundamental and existential levels as individuals, as groups, because it’s going to do it in different and drastic ways, and we’ve got few, if any, safeguards in place to

a) Protect us from the changes we don’t really want

b) Protect the parts of us and our cultures we want to preserve.

This should alarm us because we’re completely

unprepared to do anything but react.

We find ourselves waking up in the middle of a forest fire

with no idea what might be on hand to battle it, how escape intact.

‘Humans and / versus AI.” That’s really a great encapsulation of our relationship with technology, with ourselves. On the one hand, these things are extensions of various parts of ourselves as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Marshall McLuhan, and others have pointed out. It’s also ever been an uneasy relationship, hasn’t it? Adversarial – whether necessarily or not I’m not sure.

Maybe the first thing I’ll do is give you, the audience, an assignment: while you’re reading this paper, consider whether any or all of it was developed using AI. maybe that question already owns some real-estate in your head. As a teacher you’re looking at student work in a new light. As a consumer, wondering how much of what you see and hear in the world might be certified 100% Human. It’s been interesting to follow how attitudes develop, who cares about the questions and answers, and where and when they do or do not care.

I could say a lot of spicy, provocative things here just for the sake of provocation, getting a rise, getting attention. But though I might say some spicy, provocative things, it won’t be for anything but an attempt to attract attention not to myself but to some unsettling questions that deserve not just attention but action.

I’m pretty sure that even if you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve heard of AI at this point. You’ve probably heard some very alarming things, and are wondering what this means for you, your family, your community, our world.

It seems to be a big deal. All kinds of people are ringing alarm bells. You may have seen a news report like this:

Tesla CEO Elon Musk and Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak were signatories on an open letter signed by more than 2,600 tech industry leaders and researchers. The open letter called for a temporary halt on any further artificial intelligence (AI) development.

The petition shared concerns that AI with human-competitive intelligence can pose serious hazards to society and mankind. It urged all AI firms to “immediately cease” developing AI systems that are more potent than Generative Pre-trained Transformer 4 (GPT-4) for at least six months. GPT-4 is a multimodal large language model created by OpenAI — the fourth in its GPT series.

While that might not make a lot of sense to you, you can’t help wondering:

Can we survive ai?

Yes

»we’ve survived this long, and though this will likely be order of magnitude greater (speed and scale) we will survive this

No

»we will not remain the same unless we take drastic measures such as sealing ourselves off as a religious sect might. Even then…

On the ‘yes, we will survive’ side, it needs to be pointed out that this is not humanity’s first technological rodeo.

In more recent history, some of you may remember a time and world before we carried powerful miniature computers around with us wherever we went. We had to find a phone booth to make a phone call. Texting was not a thing. We may have carried a small digital camera, or held tenaciously to a film camera. We had a wallet in pocket or purse, with money and photos and ID and bank cards in it. It was expected that we might be out of touch for short of long periods of time during the day, and if we went away, you wouldn’t expect to hear from me until I got back. We buried ourselves in books or newspapers or walkmans, our faces not lit up by the gentle glows of our screens. We did not twitch at imaginary notifications.

I don’t know if life was simpler, but it was different. We were different.

A little further back, some of you may remember time and a world before the internet so connected and divided us. In that distant time and place we looked up numbers and services in the phone book, let our fingers do the walking. A newspaper carried news. We shared our hot takes with anyone who would listen but that number was generally drastically reduced, not potentially thousands or millions. Going viral hit different. Computers generally stayed in one place. Websites were cd-roms.

I don’t know if life was simpler, but it was different, as were we.

Further back still, so far back it’s lost in the misty depths, there was a time we didn’t have words or spoken language. It’s very difficult to imagine life for humans at that time. Very difficult to relate to. Almost nothing we do today bears any resemblance except the most basic human functions… and even those are drastically different.

Generation gaps are now technological and they’re quickly shrinking

But to put things in perspective, it helps to put things in perspective.

I’m actually quite taken with the “simple” act of human speech. Something we take utterly for granted, yet something so complex and beautiful. Almost miraculous.

Imagine: I can have this thought in my head, something to express. I can put it into ‘words’ and I can use my mouth and lungs and put it into sound waves carried on my breath to your ear where it’s decoded again back into words which are in turn decoded into ideas in your head… and we can, and do, do this as if it’s nothing at all?!

It’s possible that I am easily amazed, but what a remarkable thing. It never gets old.

Think about that person before words and speech. Think about what their existence was like. Think about what mattered to them, what matters to us today which wouldn’t mean a thing to them.

Fast forward some to ourselves before the internet, or more recently, before smart phones. We spend a lot of our days today doing things we didn’t do 20, 30 years ago. Things which were you to tell 30 years younger you about, that you would not believe.

Aside from the obvious aging et cetera, in very many ways you do not resemble that person. Their life.

As our technologies change, we change. Everything about us changes personally and socially.

Marshall McLuhan, to his delight, became acquainted with a book called ‘And There Was Light’ by Jacques Lusseyran, a prominent figure in the French resistance during World War Two.

As it happens, Lusseyran was born in Paris 99 years ago today.

In this remarkable book, Lusseyran recounts in detail how as a young child he suffered a playground accident that almost completely robbed him of sight. But rather than this being a story of trauma and loss, he describes how though he lost his visual faculty, he gained great increases in other faculties. His sense of hearing, of touch, became greater.

Instead of shrinking his world, it opened it up: ‘and there was light.’

Marshall McLuhan loved this account because it demonstrated vividly what he had been saying for well over a decade, that the human senses exist in a delicate balance, that the human sensorium is a complex and dynamic thing. To affect one sense is to affect all the senses. And when you juggle the senses, you juggle humanity.

When you juggle the senses, you juggle humanity.

The case of the non-sighted versus the sighted person is useful in its stark contrast, is perhaps especially vivid in today’s world, for today’s human.

Think about the daily life of a blind person. Their living situation. Performing tasks, getting information by feel, by sound. Sound and tactility have special meaning for them that they don’t for us. The visual is obviously of little importance to them except in relation to non-blind people.

The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention say that

US “children between the ages of 8 and 18 spend an average of 7.5 hours a day in front of a screen for entertainment each day.” They continue: “over a year, that adds up to 114 full days watching a screen for fun. That’s just the time they spend in front of a screen for entertainment. It doesn’t include the time they spend on the computer at school for educational purposes or at home for homework.”

I wonder, if you went back 30 years, to 1993, and read that statistic to people, what their reaction would be? Disbelief, surely.

The point is that the history of humanity is the history of great innovation and change. The people and societies before and after major (even minor) technological leaps don’t very much resemble each other.

But through it all, we’re still human.

We are new humans, but humans.

We bypassed the long, slow but sure evolutionary method for the swift and drastic and uncertain technological one. I don’t think we have a Latin classification but we probably should because we’re a far cry from ‘Homo Sapiens,’ or ‘Wise Man’. Speaking Man, Writing Man, Printing Man, Telegraph Man, Radio Man, Television Man, Satellite Man, Internet Man, Smartphone Man, AI Man….

End of Part One. Part Two coming soon. Thanks again to Doc and Joyce, Isak, the Hamilton Lugar School and Ostrom Workshop, for the opportunity to present these remarks. Keep and eye on their ‘Beyond the Web Speaker Series’ for upcoming guests speaking to similar topics.