In a Sense, Lost.

Last week, the WEF released ‘Ai Governance Alliance: Briefing Paper Series 2024.’ Authored by 250 people from 200 organizations and none of them seem to understand that 'the medium is the message.'

WTF WEF? (this is actually the title I wanted to use for this newsletter but thought it was a bit spicy)

Last week, the World Economic Forum released ‘Ai Governance Alliance: Briefing Paper Series 2024.’ Three papers from working groups comprised of 250 people from 200 organizations and none of them apparently understand that ‘the medium is the message.’

As someone who seems by nature to be more hopeful than the average person, reports like this, by 250 or so people who should know better, are cause for some deflation.

There is no meaningful regulation possible which doesn’t account for how the user is transformed personally and socially by technology. To do this, they have to do what’s apparently impossible: disregard the content and instead look at how technologies displace and create environments with particular attention to the human senses; how they are configured, how they are transformed.

I’m obviously the most biased person in the room. To me, for people involved in any capacity in technology to ignore McLuhan work is like someone in physics ignoring Einstein:

probe: ‘The medium is the message’ is for media what e=mc2 is for physics.

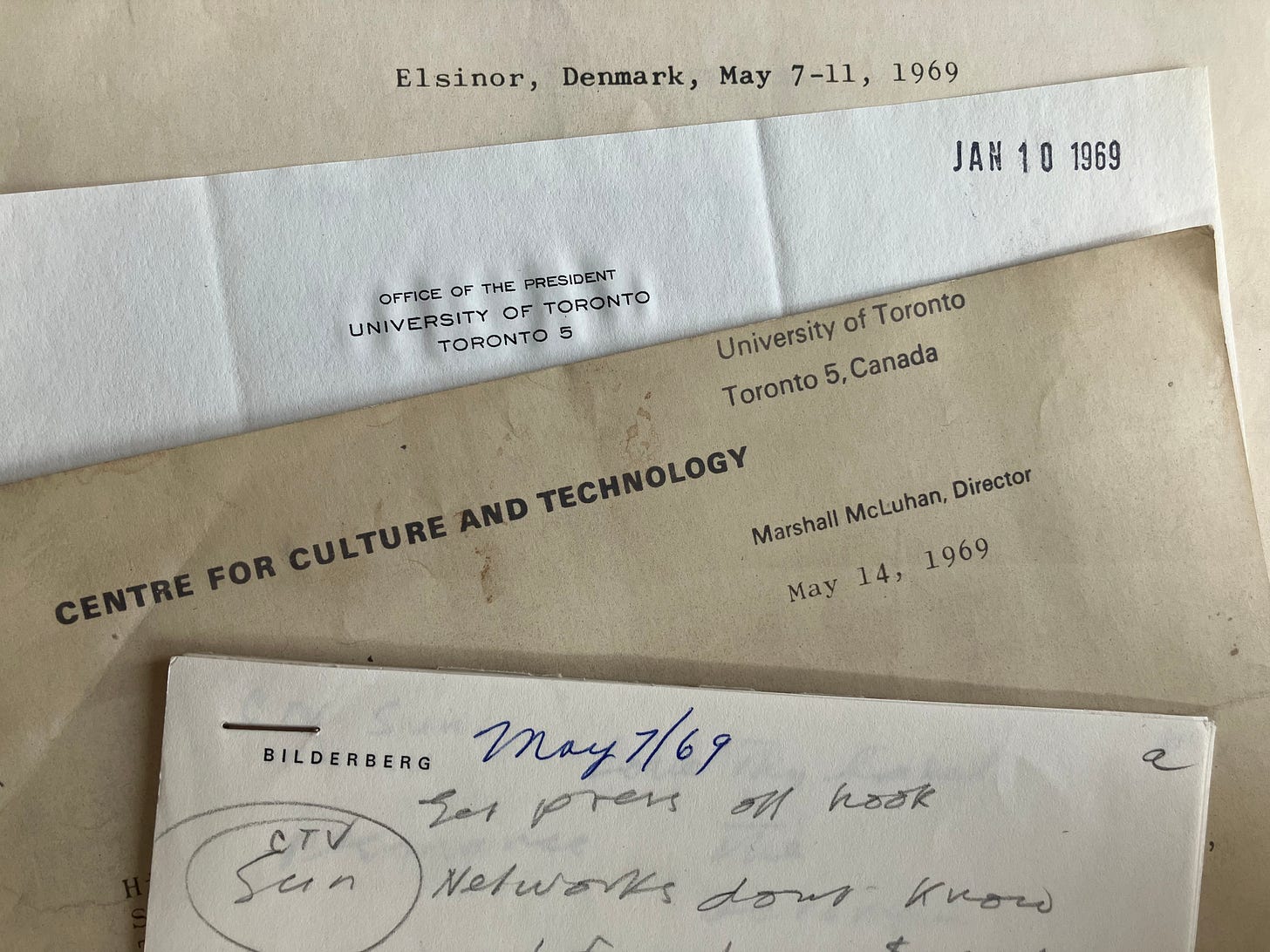

This is not going to be a extended and depth critique of the WEF reports. I’m not sure how useful that would be. Instead, I’ll go into some of what, from my perspective, is missing from the WEF to US Congress, but first I wanted to mention something that this brought to mind – that time when Marshall McLuhan was invited to the Bilderberg Group’s meeting in Denmark in 1969

Bilderberg ‘69:

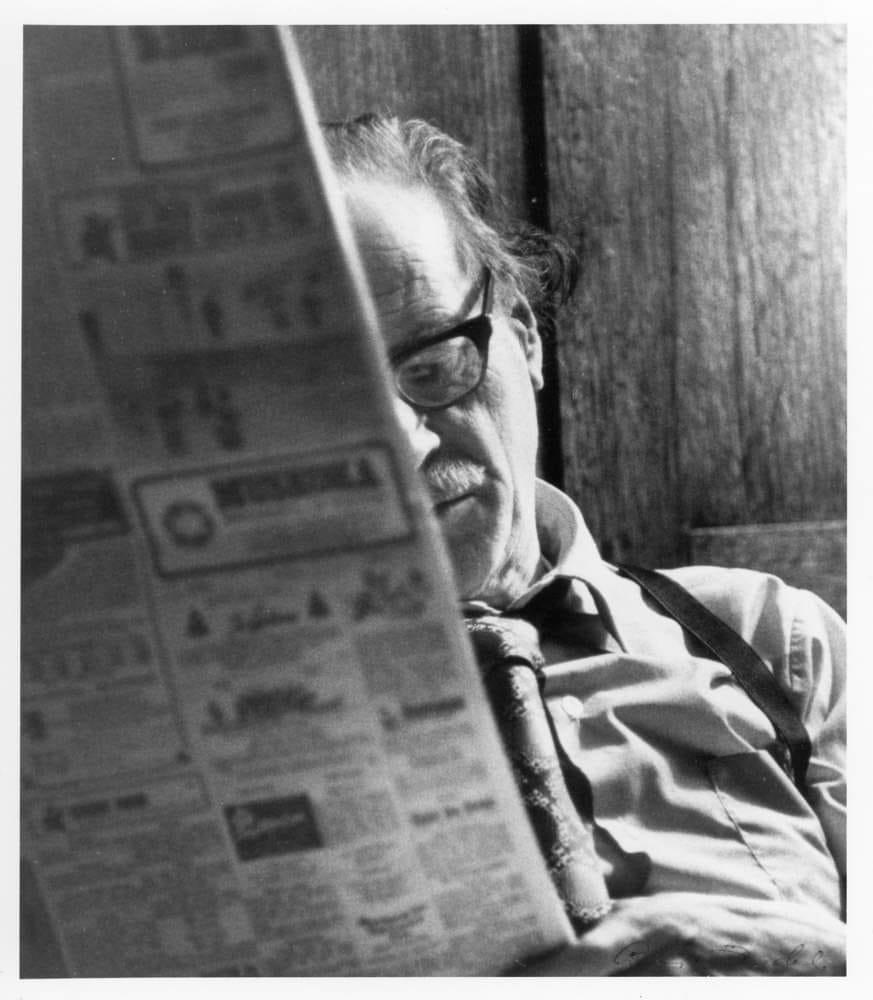

Marshall McLuhan was invited to attend and address the Bilderberg Group by then-president of the University of Toronto, McLuhan ally, Claude Bissell. He expected that these people, who were supposed to control the world, would share his understanding of how the world worked. He was shocked to learn that they were as ignorant as anyone else, that they had no real idea of what they were doing.

As his letter to His Royal Highness Prince Bernhard, Prince Consort of the Netherlands shows, Marshall was, to say the least, disappointed. The Bilderberg attendants did not at all appreciate it and likewise let it show.

“It was good to be there. It is good to be back. As you know, I was rather a bad boy at Bilderberg. Frankly, I was staggered at the very low level of awareness of the contemporary world exhibited by all the guests present… Ordinary people live thirty years back in a state of motivated somnambulism. Such was the state of the delegates at Bilderberg.” Letter, May 14, 1969.

Ouch. It goes on in the same vein:

“They were men of a few simple old-fashioned concepts… The great advantage of participating in Bilderberg is that it gives one a means of estimating the level to which the incompetence of the participants had enabled them to attain. Every man has a right to protect his own ignorance. However, these men are responsible for coping with a changing world which has sent them scurrying for cover in the opposite direction of the changes that we have released. I asked them to instance a single example in human history of any community that had been able to foresee the consequences of any innovation. The group was unable to comply.”

Marshall McLuhan, making friends wherever he went. One account I’ve seen of someone who was at that conference had equal (or greater) unflattering things to say about Marshall in return. They did not appreciate his words, or efforts. Like when, to shake things up a bit, he rearranged the chairs from the customary rows into a circle:

“I hope you will correct the unfortunate space arrangements which the participants of the conference had to endure, with a consequent loss of dialogue. If I appear to be rude, it is because I am not addressing myself to persons, but to issues of great urgency.”

It was ‘great urgency’ in 1969. Fifty-five years ago. I’m not sure how to upgrade the urgency to account for the increase in speed, scale, and consequence of today’s suite of innovations taking place with AI, but ‘existential urgency’ might not be an exaggeration.

I wonder, if Marshall were alive today, if he was invited to speak at Davos, what would he say? More importantly, would anyone listen? Judging by the papers released yesterday, I have to think they wouldn’t listen: but I’m going to say my piece anyway because it needs to be said and maybe someone who is in a position to make a difference will take note and take action. I’m going to say my piece. It’s probably not what Marshall would say today but I’ll draw on things he said 50 years ago because they’re still useful. Many of his observations on the nature and effect of technology remain useful because he tended to study innovation as a category and not simply individual technologies.

This one is in honour of my grandfather, who never lost hope in the face of great odds, and in honour of my father who would have turned 82 today (I started writing this January 19th) if he hadn’t died in 2018. My father, working diligently for decades after the death of his father, is the reason there is any McLuhan legacy left for me to try to carry on.

To the present, or the most recently perceptible past (whichever comes first):

It’s 2024, we are releasing ever-more-powerful technologies and we’re still only talking about regulating at the content-level. The world is still ignoring the basic fact that the medium is the message.

‘Content is King’ is the war-cry of the modern somnambulist. If content is king, it’s as in charge as the president of any country, which is to say it has the appearance of power but the reality is that it’s not running the show. Content is great. Content is important. But content doesn’t account for the power of technology to rearrange who we are except in its power to hold our attention and distract us while the medium does that job.

Content is the spoonful of sugar which helps the medicine go down.

‘The medium is the message’ is a poetic statement, and like poetry, making meaning is more the reader’s than the author’s job. Those five words take a bit of work to unpack, but why shouldn’t they? The truth is that media are slippery things. Like gravity, like the presence of an invisible star, media elude direct perception. You measure influence by effect. You have to get poetic.

Making Sense:

“Very few people know what ‘the medium is the message’ means because they’ve never asked. The medium is the thing that changes. The program doesn’t, the content doesn’t, but the medium is always changing because it is the ground itself.” ‘Monday Night Seminar’ February 5, 1973 (a wonderful listen)

‘We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us,’ is how John Culkin summarized ‘the medium is the message’ in his 1965 article ‘A Schoolman’s Guide to Marshall McLuhan, by paraphrasing Winston Churchill who said in 1943 “we shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.” Hopefully by the end of this newsletter, you will begin to appreciate how profoundly we are shaped, that we are in the process of being reshaped by AI as it swallows our world and regurgitates us.

‘The medium is the message,’ or m/m as McLuhan often shorthanded it in his annotations, is a lot like Einstein’s formula: ‘the increased relativistic mass of a body times the speed of light squared is equal to the kinetic energy of that body,’ or e=mc2. Both are complicated, compressed ideas. I’d bet as many or fewer people understand well enough to explain, if asked, what either means. It’s interesting that Einstein’s formula, perhaps the more difficult to explain and understand, is taken for granted by most while McLuhan’s is hardly taken into consideration at all. The reasons for that are too many to outline or explore in this note but it is telling that Canada doesn’t have much more than a stamp and a plaque to honour one of its greats who was a global household name for most of a decade.

.

The way I usually go about helping people unpack ‘the medium is the message’ is to show some of the many examples of McLuhan using the phrase, or the ideas behind it. For example, three years before he hit on the m/m formula (he first said ‘the medium is the message’ in 1958) he understood the idea:

“And until we understand that the forms projected at us by our technologies are greatly more informative than the verbal messages they convey we are going to go on being helpless illiterates in a world we made ourselves” ‘A Historical Approach to the Media’ 1955

Four years before he wrote the evergreen guidebook on understanding media, McLuhan wrote a lengthy piece on its underlying principle in an article titled ‘The Medium is the Message’ in the ‘Houston Forum.’

“It is the formal characteristics of the medium, recurring in a variety of material situations, and not in any particular ‘message,’ which constitutes the efficacy of its historical action.” ‘The Medium is the Message,’ 1960

You can’t just read McLuhan’s statements, or Einstein’s formulas, once and move on. Physics, like poetry, require more from you if you want to get anything from it. A common mistake people make is trying to read McLuhan as if it’s any other text written to serve up understanding. It’s more like a meal in a box than a personal chef: the ingredients are all there but it’s up to you to put it together. To be sure, not everyone is up for that. My object here is to give you a helping hand, but you still have to get involved. Or not. Your choice.

My suggestion, my invitation, is to take the statements in this edition of the newsletter and chew them over. Read them like a poem, a haiku. Re-read them. Think about them over the day. Try them out.

“The medium is the message means … that a totally new environment has been created.” ‘Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man,’ 1964

“The section on ‘the medium is the message’ can perhaps be clarified by pointing out that any new technology gradually creates a new environment. Environments are not passive wrappings but active processes.” Introduction to the second edition of ‘Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man,’ 1966

“The medium is the message because the environment transforms our perceptions governing the areas of attention and neglect alike” ‘Postscript 1970’

“A medium works on you much like a chiropractor or some other masseur and really works you over and doesn’t leave any part of you unaffected. It is a process and it does things to you. The medium is what happens to you and that is the message.” In ‘The Telegram Weekend,’ 1967

“It is the medium itself that is the message. It literally works over and saturates and molds and transforms every sense ratio. The content or message of any particular medium has about as much importance as the stenciling on the casing of an atomic bomb.” Interviewed in Playboy Magazine, 1969

Making Sense: we are the sum of our senses.

A quick response to the WEF’s AI Governance papers would be this 1962 statement:

“A theory of cultural change is impossible without knowledge of the changing sense ratios effected by various externalizations of our senses.” ‘The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographical Man,’ 1962, recipient of the Ontario Governor General’s Medal for Non-Fiction

Nothing I read in the WEF papers reflected this basic fact of the individual and social effects of technologies: that technologies, as externalizations of our senses, they affect our senses in return, changing their nature and operation, and that these changes change who we are at fundamental levels. Individually and socially our perception, knowledge, tastes, and much more are shaped by the quality of our senses individually and operating as a whole. Our identities are the sum of our senses. We are what we perceive.

I’d suggest we can modify the statement from the Gutenberg Galaxy to read:

‘Regulation of technology is impossible without knowledge of the changing sense ratios effected by human technology.’

We don’t seem to have, at levels like the WEF and FDA, that knowledge, though we do have many more methods available to us today that we didn’t in 1962 for measuring the effect of technologies on our senses.

“Going along with the total and, perhaps, motivated ignorance of man-made environments, is the failure of philosophers and psychologists in general to notice that our sense are not passive receptors of experience.” ‘Identity, Technology, and War,’ 1970

The first main point in that statement concernins ‘man-made environments,’ which is another way to say ‘medium’ in McLuhan terms. In ‘Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man,’ chapter 4, ‘Narcissus as Narcosis’ deals with why it is that when we extend a sense (technologically), we numb ourselves. He draws on the work of Hans Selye to do so noting that numbness is a common reaction to stress. When we are injured, often times we don’t feel the full effect of the injury the moment it happens. It’s a survival instinct. We put off the pain until we are safe.

In technological terms today, we’re never ‘safe,’ out of danger. The speed and scale of technological development and impact insures that we move from injury to injury with little respite. It’s no wonder we and our world look the way we do. One could say we’re suffering from a collective technologically-induced ptsd, except we never get ‘post-trauma.’ A change is not as good as a rest.

The second part, “the failure of philosophers and psychologists in general to notice that our sense are not passive receptors of experience,” is no less concerning. It goes to the transformative nature of our technology, how we are ‘shaped.’ It is actually the key to understanding the impact of technologies themselves on us, not their content. The content is actually the delivery mechanism for the change. It is while the senses are engaged that they are shaped – that they are not passive receptors, but that their stimulation has an impact on the nature, the quality of the senses: they are retuned.

The other key piece here is that our senses do not operate alone, but exist in a balance among themselves – and who we are is a result of the influence of that balance among our senses. You mess with one sense, you mess with the relationship between all the senses. You mess with the relationship between the senses and you mess with who we are. Not only our self-constructed identities (which anyone can see is very much in flux, confused in the extreme) but also our actual being.

Take away sight (or any other sense) and you obviously drastically change someone’s preferences across the board. While that is an extreme case, you don’t have to completely remove a sense in order to have a profound impact. Slight changes in our sensory systems can have great changes in our perception, our experience, our lives.

I read a comment online: “we can’t trust technology we can’t control.” If we aren’t paying attention to how technologies impact our senses, the very foundation of ourselves and our cultures and institutions, how can we control them? We are ignoring the very mechanisms by which we are controlled. We are applying the equivalent principles of censorship, and there are just as effective.

If we have an inadequate notion of what control means, it’s because we have a very incomplete understanding of technological change.

Again: ‘A theory of cultural change is impossible without knowledge of the changing sense ratios effected by various media.’

Marshall McLuhan distinguished his approach from others’ by saying:

“My kind of communication is a study of transformation, whereas information theory and all the existing theories of communication that I know of are theories of transportation.” ‘Living in an Acoustic World,’ 1974

“Mine is a transformation theory, how people are changed by the instruments they employ.” ‘Living at the Speed of Light,’ 1974

Content:

The critical part of this situation is that the content of any medium is not the deciding factor in its effect. It is the smallest factor which receives the biggest attention, and that needs to change as our ability to make staggeringly impactful technologies becomes easier and faster.

“Many people would be disposed to say that it was not the machine, but what one did with the machine, that was its meaning or message. In terms of the ways in which the machine altered our relations to one another and to ourselves, it mattered not in the least whether it turned out cornflakes or Cadillacs. The restructuring of human work and association was shaped by the technique of fragmentation that is the essence of machine technology.” ‘The Medium is the Message,’ 1964

It turns out that, paradoxically, the content is the delivery mechanism for the effect of the medium. It is what keeps our attention while we are being reshaped on an individual and cultural level.

It is amazing that at this point in history, where we’ve advanced so far in our understanding of so many areas, we remain so unsophisticated in this most consequential area. Our level of awareness is that of medicine before we were aware of the existence of bacteria.

“It is, however, no time to suggest strategies when the threat has not even been acknowledged to exist. I am in the position of Louis Pasteur telling doctors that their greatest enemy was quite invisible, and quite unrecognized by them. Our conventional response to all media, namely that it is how they are used that counts, is the numb stance of the technological idiot. For the ‘content’ of a medium is like the juicy piece of meat carried by the burglar to distract the watchdog of the mind. The effect of the medium is made strong and intense just because it is given another medium as ‘content.’ The content of a movie is a novel or a play or an opera. The effect of the movie form is not related to its program content. The ‘content’ of writing or print is speech, but the reader is almost entirely unaware either of print or of speech.” (1964)

What Can We Do?

In a remarkable essay McLuhan wrote in 1965, just after ‘Understanding Media’ was published, and which he circulated widely, he concludes:

"The need of our time is for the means of measuring sensory thresholds and of discovering exactly what changes occur in these thresholds as a result of the advent of any particular technology. With such knowledge in hand, it would be possible to program a reasonable and orderly future for any human community. Such knowledge would be the equivalent of a thermostatic control for room temperatures. It would seem only reasonable to extend such controls to all the sensory thresholds of our being. We have no reason to be grateful to those who juggle the thresholds in the name of haphazard innovation." ‘The relation of Environment to Anti-Environment,’ 1965

Given that the change of most import comes from the impact of media on our senses, and the corresponding rearranging of our senses provoking a rearranging of human sensibility, preference, experience and endeavour, we need to pay a lot more attention to our senses if we want any control. We need to pay attention to how the senses work individually and together. How we are the sum total of their configuration. How that configuration makes certain people and cultures possible, and that to change that configuration is to remove the very structure of support from under it all.

Following this 1965 essay Marshall tried to make this happen, because he was sick of humanity having merely the illusion of control over its destiny. He knew people in high places, but if he tried to, he was unable to convince them to act.

“Awareness of the sensory and perceptual effects of diverse technologies can make possible a human and modest existence for those who seek it.”

Marshall McLuhan TSS dated February 28, 1973

I wanted to publish these remarks last week, but though I assembled the bulk of it then, I needed time to try and get it right. I usually write a post in a few hours. This one I’ve dipped in and out of for the last week, added bits, cut bits, tried to find a conclusion.

I also don’t want to devalue what must have been a lot of hard work by a lot of very capable and highly qualified people that went into the WEF reports. I’m not trying to dismiss that work, but to add to it some things which appear to be absent. Echoing Marshall’s post-Bilderberg apology: “if I appear to be rude, it is because I am not addressing myself to persons, but to issues of great urgency.

It’s wild that more than half a century later, we seem to have made no progress toward the issues Marshall raised to world leaders in 1969. Knowing he wouldn’t be surprised, I wonder what he would say. Would he think we’ve made progress? Would he still be hopeful?

It’s hard to know where to go from here. What’s the point of demanding change when we don’t seem to know what change we need? There’s a very real prospect that if we actually took control of technology at this level that we could make things much worse. Maybe we refuse to recognize that ‘the medium is the message’ and refuse to act accordingly because of some primal instinct that even if it’s knowledge and control within our grasp, it’s beyond our safe handling.

If the WEF AI Governance reports are anything to go by, we are in no danger of that any time soon.

Postscript: we’re just about a year into this newsletter. I want to thank everyone for their attention and subscription. My object here is to bring McLuhan into conversation with the issues of the day, blending the work and words of my grandfather Marshall McLuhan, my father Eric McLuhan, with my own attempts to translate them into something useful today. Your support in this effort means the world. Thank you.

Frank Zingroni was my favourite professor at York. One time he and your father addressed a large group of us in one of the big lecture halls. Probably 100 students.

They were hilarious and irreverent. They were very much mentors to me.

OK the medium is the message, my understanding 35 years later.

Electricity ended our mechanical reality by introducing lightspeed into human affairs thereby usurping time and space. All knowledge became available, instantaneously available with the consequence that our world imploded into a new type of Village. We live cheek by jowl and are subject to a deafening din of all voices all at once.

After 3000 years of specialization, explosion , owing to mechanical technology we have through the auspices of electricity, extended our central nervous system and consciousness to envelop the planet. Electricity is in effect and implosion and it put our world of explosion into reverse. With this we return to our spiritual roots as a tribe, holistic, desiring of experiencing things and people in totality and demanding emancipation from imposed patterns. He said there is a spirituality this new way, sans the limitations of time and space.

OK that’s enough.

I’m very glad I found you. Your grandfather and Plato‘s republic are my primary sources of understanding.

My name is RJ France I live in Toronto and I’ve been the owner of a security guard company called Paragon Security for the last 30 years. I fancy myself as Plato’s philosopher king.

Your grandfathers ideas are lost at our peril . He was correct beyond debate and the nature of his discovery, that technology shapes us, regardless of content, must be accounted for in all considerations, and as a precursor to all disciplines of inquiry.

I have found another example of this : Curtis Yarvin’s gray mirror, substack: a brief explanation of the cathedral. Like the medium is the message, the cathedral effect must be accounted for, in all circumstances: “

the selective advantage of dominant ideas, and the inability of recessive ideas to compete” must be taken into consideration and always.