Is the Medium (still) the Message?

The medium is the message—so what? You might as well say ‘climate change—so what?’

Our technologies change who we are individually and collectively as surely and as profoundly as climate change reshapes the Earth and everything on it.

When the spoken word changed humans; how we interact, and the quality and depth of interaction, forever, the medium was the message.

When the word in song or rhyme allowed cultures to transmit knowledge and values across space and time, the medium was the message.

When the written word allowed humans to communicate further than their voices could carry, the medium was the message.

When the telegraph allowed humans to send messages at light speed and all levels of personal, social, political, and commercial interaction were instantly changed forever, the medium was the message.

When the telephone allowed us to talk to each other across the world as easily as across the room, utterly transforming humans and how we do things, the medium was the message.

When the answering machine meant we didn’t have to wait around for that phone call and could instead get on with our business, the medium was the message.

When the cell phone cut the cord and allowed us to make and take telephone calls from anywhere, anytime, to anywhere else, the medium was the message.

When the smart phone put not only a telephone but a camera and much more in everyone’s pocket, the medium was the message.

Today, as AI and a host of other new technologies reshape our world and our selves at a blinding and mind-numbing scale and speed the medium is the message, because like climate change, these changes alter everything about us: who we are as individuals and cultures, how we imagine ourselves, what we value, prefer, find tasteful or congenial, distasteful or jarring.

When media change we change fundamentally and permanently, and that’s kind of a big deal.

“Societies have always been shaped more by the nature of the media by which men communicate than by the content of the communication. The alphabet, for instance, is a technology that is absorbed by the very young child in a completely unconscious manner, by osmosis so to speak. Words and the meaning of words predispose the child to think and act automatically in certain ways. The alphabet and print technology fostered and encouraged a fragmenting process, a process of specialism and of detachment. Electric technology fosters and encourages unification and involvement. It is impossible to understand social and cultural changes without a knowledge of the workings of media.” (McLuhan and Fiore, ‘The Medium is the Massage,’ 1967)

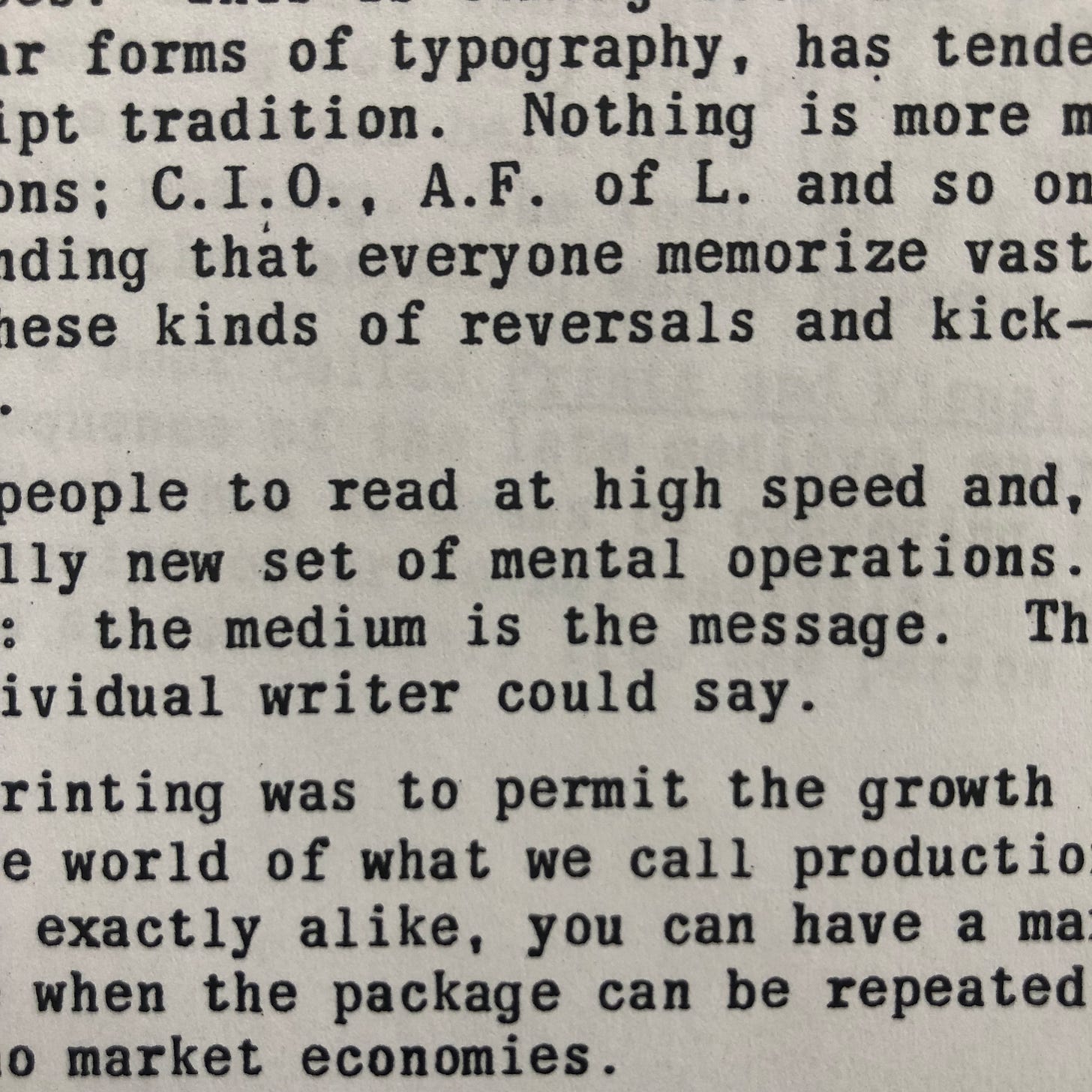

When Marshall McLuhan first said, during his speech at a radio broadcaster’s conference in May 1958, that the medium is the message, that

“The medium of print is the message, more than any individual writer could say,”

it likely received two main reactions. The main reaction was probably ‘that’s nonsense.’ A smaller group may have thought ‘that’s brilliant.’

Today, it’s almost a given. To point out that the effects of print technology itself as an individual and social shaping force was much greater than the content of what was printed, happened regardless of what was actually printed, is obvious. It’s obvious now that the transformational power of the form is much greater than that of its content. It is hard to imagine a time when to suggest that was radical.

To say in 1958, that ‘the medium is the message,’ was a provocative, radical thing to say. It is still a provocative thing to say, at times radical depending on the company, but the truth of it is perhaps more plain to see. That essentially our entire way of living, across the globe, is dependent on something like electricity or internet or smartphone, and that if these things were to disappear we would face utter chaos—that is a very big deal. And it’s more than that: who we are on every level is shaped by the technologies we use. They envelop us, surround us like the air we breathe. They shape and reshape our senses and minds, our values and preferences, our likes and dislikes, ourselves individually, our families and cultures.

This is what media are doing while we’re busy creating content: they’re creating us. Today, technology develops so quickly that … well, I don’t have to tell you how it feels. You’re living it.

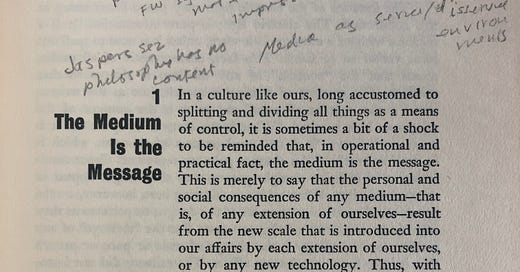

“…in operational and practical fact, the medium is the message. This is merely to say that the personal and social consequences of any medium -- that is, of any extension of ourselves -- result from the new scale that is introduced into our affairs…”

In 1958 there was no such thing as media studies. The closest thing was in communication(s) or some part of literature studies. The term ‘media’ was not widely used mainly because it was not really an area of study or even attention. One of Marshall McLuhan’s remarkable achievements was introducing ‘media’ as a category of study. Not simply communications media, but all human innovation: “from Cadillacs to Corn Flakes,” from clothing to housing, to games; from the alphabet to telephones to televisions and far beyond to include

“anything man makes or does.”

When you point it out, it’s obvious that the medium is the main agent of transformation. It is what it does. It’s hard to argue against. Given our conceit and obsession with content, it’s often easier to make the case against the medium using an example of something less traditionally regarded as a medium, like clothing, or air conditioners, because these things don’t have a lot of what we consider ‘content,’ so it’s much easier to perceive the effect of the medium itself.

A world without clothing is a world less widely populated by humans. There’s an argument to be made that we’re not ‘meant’ to live anywhere else, as we can’t without various supportive technologies. Without clothing, we’re confined to warm places. We would have little or no sense of physical modesty. Our attitudes toward the appearance of our bodies must surely be radically different. Not to disrobe, but to cover ourselves might be exotic, titillating.

The kind of human and human society which exists because of heating or air conditioning has nothing to do with what conversation we have in a room or building with air conditioning. It has everything to do with the kinds of buildings we can have because we don’t have to rely on the natural climate. The kind of lifestyle and work which are possible because of the comfort provided. That as long as the electricity holds out, we can keep working through the hottest or coldest day, sleep comfortably or work through the night. Structures can soar into the sky. The hottest region is as cool as you like, the coldest region is tolerable.

In the same way, the commute of our time is online rather than on the river, the highway or train track. In the earlier 20th century, the highway and automobile collided to create the suburb and the commute. These had drastic effects on work life, home life, on the city and on the countryside, on everyone in the family, who now had new roles, new relationships, and new identities. They were driven into completely new personal, social, and professional relations. A new culture was conceived.

Now, as more and more people do more and more work from home, again the existing structures, roles, identities, relationships, are overturned, supplanted, reshaped, reformed.

Without its foundation, any structure will eventually collapse. Even though a scaffolding may be erected to hold up a structure by brute force for a time, we feel the structure sway and know that all is not well.

When you work from home, it’s harder to leave the office. Some never do. The office no longer needs an entire building. Parents can be more (or less) present for their children. That meeting doesn’t need to be in-person. That conference doesn’t either. That class. That health appointment. All these things are restructured, and this restructuring is an effect of the form, of the medium, which reaches the shore and ripples back leaving motion sickness or chaos in its wake.

This is obvious. I don’t even have to point it out. Except that if I hadn’t pointed it out, it wouldn’t be so obvious.

Perception is a funny thing. We’re of two minds about it. We tend to not notice things when they’re running smoothly, as they should. It’s when things go wrong that they drift up, sometimes jarringly, and demand our attention. As with our physical health: when all is well, we don’t notice it. Or like when on a hot summer’s day the power goes out and so does the air conditioning and all of a sudden it seems like we should have built that high rise with windows that opened, or maybe not built that high rise at all.

Media, as extensions or amplifications of our individual or collective selves, operate beneath our notice when they run as they are meant to. But as our bodies or a car engine overheats when its optimal conditions are exceeded, it quickly becomes apparent that either we take a break, or we break. It could be that we are redlining right now, have exceeded our capacity to cope, and might consider slowing down or taking a rest, or risk damage we can’t easily repair.

The difficulty with media is that so much happens beneath our notice. We might feel the effect, but either not see or just ignore the cause. And so it helps to be reminded, from time to time, that

“in operational and practical fact the medium is the message.”

The good thing about an environmental disaster is that it’s usually pretty easy to diagnose the problem. That’s partly because we’ve turned our attention to those sorts of problems, and develops means of measuring and testing and solving these problems.

When the fish turn belly up and wash up on shore; when the water makes your skin itch and gives the kids ear infections; when you turn on the tap and it shouldn’t be that colour—when these things happen we go looking for answers because we know that something’s not right. We know there’s been a change in the environment that’s resulting in these outcomes. It becomes pretty clear pretty quickly that the chemical plant on the other side of the lake has a leak, and that something should be done about it—or that we should do something about it. Few companies are likely to volunteer to spend money cleaning up their messes, they’re generally compelled to do so when public outcry becomes impossible for politicians to ignore.

The bad thing about the effects of media is that it’s harder to track the pollution to its source. It doesn’t help that we do our best to ignore the man-made origins of our media malaise. I suppose few people want to admit to their own mistakes. Certainly, companies do not like to admit fault.

When something makes us physically sick, we know how to evaluate symptoms, diagnose the problem, prescribe a solution.

Media don’t always work that way. The environment created by technologies is difficult to perceive, the effects as elusive as they are profound. As Marshall McLuhan put it in the first chapter of ‘Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man’ in 1964:

"I am in the position of Louis Pasteur telling doctors that their greatest enemy was quite invisible, and quite unrecognized by them.”

And, a bit later:

“…so the latest approach to media study considers not only the "content" but the medium and the cultural matrix within which the particular medium operates. The older unawareness of the psychic and social effects of media can be illustrated from almost any of the conventional pronouncements.”

Causality in media can be a slippery thing indeed, and Marshall McLuhan’s method was to rely not on a (single) point of view or perspective, but on as many as possible. Because often to get the most complete picture of a situation or object, you need to see it in more than two dimensions.

This book aims to provide just such a multi-dimensional scan of what a medium is so that we can, collectively, understand what it is that the medium is the message. To understand that it’s not to say that content doesn’t matter, but that when it comes to how humans change individually and collectively with our media, it’s from the medium and not the messages – in fact, the messages only get in the way of seeing the medium for what it is.

“For the "content" of a medium is like the juicy piece of meat carried by the burglar to distract the watchdog of the mind.”

Why now?

Some years ago, I was trying to get a friend to sign up his staff for my workshop on ‘the medium is the message.’ He asked me what the value would be, and that shut me up for a second. It sounded to me like he was asking ‘why study media?’ and the answer seemed ridiculously obvious… and yet I didn’t have an easy answer. I asked other people ‘why study media?’ I asked media studies professors, and no one had answers which satisfied me. I finally figured out that the best, if not easiest answer is: because the medium is the message.

Possibly the best argument for trying to understand media is just that you don’t need to understand anything about a medium for it to completely rearrange you and your culture; your preferences, tastes, values.

Neither disproval nor ignorance are immunity.

Like advertising and propaganda, the less attention you pay, the more effective it is. People really don’t seem to be aware of how tied our identities are to our technologies. The digital is already our twin. Who we are individually and collectively in an age ruled by print culture, print speed, is not possible at internet speeds. Western values, as formed by the structure of alphabet, literacy, press, are dependent on those structures and without that structural foundation, are lost. We see their wreckage around us even as we cling to its tattered remnants.

If at any point we decide we like and wish to preserve who we are and what we stand for, we would be wise to carefully consider that the medium is the message and act accordingly.

In the last few centuries, since electricity in particular, we’ve increased the speed and scale of technologies to extremes the world has never seen. In the past, technological change took time, and humans could keep pace. The disadvantage of this incredible speed of innovation is the advantage to, for the first time, notice what’s going on.

Marshall liked to quote Bertrand Russell as saying ‘if we only raise the temperature of the bath water by half a degree every hour, we wouldn’t know when to scream.’

In the past, technologies took longer to develop, longer to implement and spread, longer to reshape us and the world. A half a degree every hour. When we have time to get used to the temperature, we adjust, and all is well.

Today, we move at the speed of light, and humans weren’t built for the speed of light. It seems every time we try to take a step, it’s as if into boiling water. It’s painfully obvious that we need to do things differently if we don’t want to keep getting burned.

So what do we do?

First, we need to back up a step. “Diagnosis before prescription.” We need to get a handle on the situation, as complete a picture as possible. We need to achieve an environmental awareness such as we did in the mid-20th century when, with a silent scream, we became aware that we were destroying our planet by our actions and inaction. We have yet to achieve that awareness, collectively, about the fact that we’re doing the same thing to ourselves and our cultures with our technologies. Earth is much more robust than we are.

By sharing a multitude of examples of Marshall McLuhan explaining that ‘the medium is the message,’ this book aims to help achieve that goal: because the first step in proposing a solution to any problem is identifying the nature of the problem, and when it comes to the most pressing existential questions of our time,

The medium is the message.

Andrew McLuhan

June 2023

The preceding was composed to be an introduction for the book I’m writing on ‘the medium is the message’ which I hope to publish via printing press in the near future. Given the likelihood of that coming to pass, I’m publishing it here instead. To support more work like this, please consider a paid subscription to this newsletter.

Images used in this article are of Marshall McLuhan’s annotations in a copy of ‘Understanding Media,’ and a copy of Ezra Pound’s ‘ABC of Reading,’ and of the transcript of his 1958 speech at the University of British Colombia, where he first publicly stated ‘the medium is the message.’

Great post - and I look forward to following you more closely. Kool to learn you are 'the grandson of' a sixty's/pepsi generation icon that I and my fellow boomers revere! I get a kick out of referencing his prescient words often in my writing. And, in terms of your newsletter, your grandfather would, I'm sure, be very proud!

So ... is “the medium” still “the message”? Or is “the medium” ... “the Rearview Mirror”?