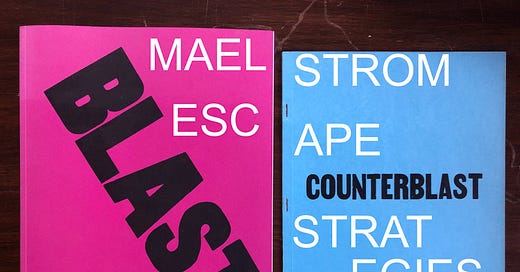

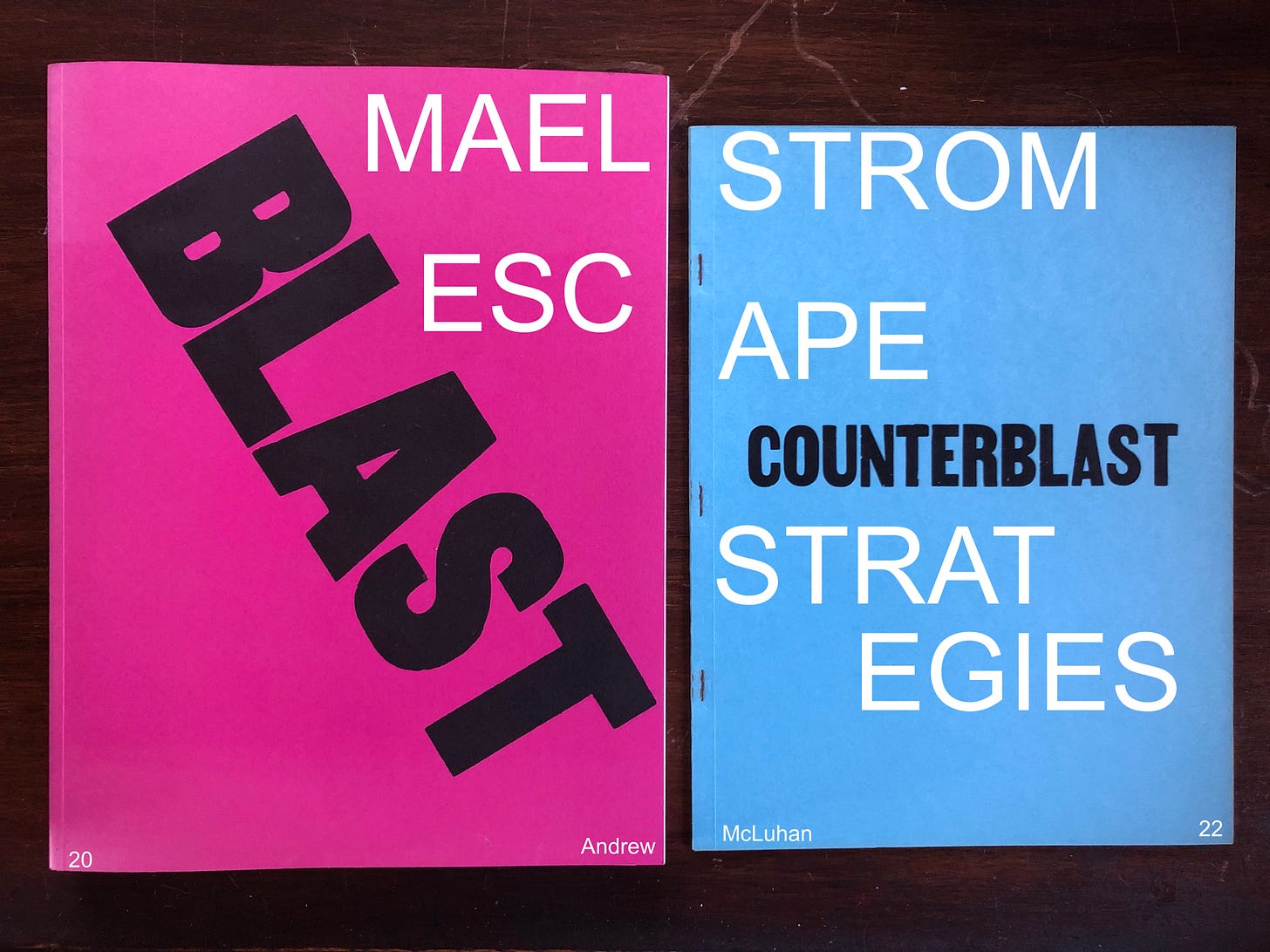

Maelstrom Escape Strategies:

Enter the Vortex

I find myself in good company. Charles Dickens, James Joyce, Agatha Christie, and Hunter S. Thompson, are among the many authors whose work I enjoy who serialized their work at one time or another. Publishing in instalments can have several benefits but I think that most turn to the device out of necessity, as I am doing.

‘Maelstrom Escape Strategies’ was written up by myself a year ago, in the spring/summer/fall of 2022. You could say it took a few months, a few years, or three generations to write, as it depends heavily on work my father and grandfather did going back the better part of a century.

You could even say it goes back almost two centuries, as it goes back to ‘A Descent into the Maelstrom’ (1841) by Edgar Allan Poe – who also serialized his work, as it happens. I’m sure if you looked you would find earlier traces still.

The present work owes its more immediate debt to, first, Reggie James and Eternal, Inc. Reggie says: Maelstrom Escape Strategies was originally produced as research for Eternal. And now we are open sourcing it for you. (Reggie didn’t ask me to plug his newsletter ‘Product Lost’ but I will because it’s excellent. As it happens, his latest ‘Issue 091: The Body as Mixer’ opens with a Marshall McLuhan quote.) Reggie had vocally supported my work with The McLuhan Institute for a while, but put his money where his mouth is too and offered me a grant, which I used to fund time and work on the Maelstrom Escape Strategies. Thanks, Reggie.

Some additional support came from my friend Chris Perry, Chairman of Futures at Weber Shandwick. He was kind of enough to lend me a desk while I was in New York last September and I used that space and time to put the finishing touches on this project. (Chris didn’t ask me to plug his newsletter ‘Perspective Agents’ but I will because it’s excellent. ‘Bicycles for the Mind’ is his latest.) Thanks Chris.

Thanks also to you, subscribers who support this newsletter, and by extension, this work. Your support is very much appreciated.

‘Maelstrom Escape Strategies’ really speaks for itself, doesn’t need much from me in the way of introduction except maybe to set the stage:

I set out to take metaphors literally, and literal things metaphorically, in keeping with the McLuhan tradition. I thought, ‘ok Marshall, we’re drowning in it. If we were already pretty far gone in the 60s and 70s, we’re all but lost now’. I figured what we needed was non-metaphorical ways of getting out. Things that we all can do, because it’s late in the game and no help seems to be coming from those we might expect to be giving it.

That’s about it. I hope you enjoy this series, and more importantly, that it is helpful to you.

Andrew McLuhan

Bloomfield

March 10 2023

Preface to a Maelstrom

My grandfather, Marshall McLuhan, spent the last decades of his life engaged in exploration. He considered himself not a theorist but an explorer. He was interested in discovery. He was interested in human innovation and how it affects us individually and societally. How the things we create reshape ourselves and our world. My father Eric McLuhan, his eldest son, eventually joined him and together they continued this exploratory, pioneering work. They were interested in not only probing and discovering the nature of this process of human innovation and its effects, but in developing tools to further that goal; much as explorers of days gone by used a compass, a sextant, or sometimes just wet a finger to feel the wind’s direction.

Here I am, in their wake, so many years later. Where Marshall and Eric came to the work from the study and teaching of English Literature, my background is in making poetry and punk rock. My approach is a little different, but my object is similar. My goal is to learn all I can about my ancestors’ work, and to wring and distill from it every drop of useful information that can help us understand today and head forward with as much understanding and agency as humanly possible. I believe there’s a lot of help in their work to assist us in turning the scales from weighing heavily on the side of ‘unintended consequences’ and more on the side of ‘human flourishing’.

“The influence of unexamined assumptions derived from technology leads quite unnecessarily to maximal determinism in human life. Emancipation from that trap is the goal of all education.”

(‘The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man’ 1962)

“Determinism is the result of the behaviour of those determined to ignore what is happening around them. Recognition of the psychic and social effects of technological change makes it possible to neutralize the effects of innovation.”

(letter, Life Magazine March 1, 1966)

“As James Joyce said of these man-made environments, when invisible they are invincible. To free ourselves from the invincible effects of our own programs of organized activity, it is necessary that we inspect the ignorance systematically engendered by our applied knowledge.”

(‘At the Flip Point of Time – The Point of More Return?’ )

“Before out time, change took place so slowly as to be invisible. Now it is so rapid that we can see the process of change. We are the first age for which this is true: understanding this is a beginning point in the Age of Circuitry.”

(‘Circuitry,’ 1966)

This work is about change, the role we play in the cycle of innovation, the people and cultures we create as a result. It is built on the premise of human understanding and agency, and the promise of same. It is built on hope, but not an abstract wishful thinking; a suspicion bordering on certainty that as much as we are the creators of our unnatural environments, we are also the liberators of our selves. Human ingenuity got us into this mess, and human ingenuity can get us out of it as well. It may not be easy, but it may not be impossible either.

I have hope, in part, because people before me had certainty. I have hope because I look around me and as much as I see that hurts my heart, I see more that lifts me up. Sometimes it can appear as if the world is a pretty awful place, and at times it is. At the same time, it’s also a beautiful place filled with things to fire the imagination and fill the heart. Often, it comes down to a matter of perception and perspective.

In our lives, our families, our communities, our world, we can feel pretty small. We can feel pretty ineffective. What can I do? The fact is, I can do a lot. You can do a lot. Little things add up to big things, and this can both work for or against our favour.

Two of the major factors addressed in this work are speed and scale. We left evolution in the dust as we sped and scaled past our bodies’ capacity to adjust. Our bodies, our minds, were not built for great speed and scale, and our inability to cope leads to a lot of pain and misery. There are certainly factors beyond our individual control. There are also factors quite within our control, and my purpose is to suggest some and to encourage you to find more which will be effective for you. To the factors beyond our individual control, we will require a collective effort in order to force the hands of those who have any power.

Put plainly, until we get pissed off enough there simply won’t be the political will to address change on a systemic level: there’s certainly no desire from industry to slow or scale anything down. Without an intervention of sufficient scale (ironically) to force the matter, political or industrial solutions are likely to come about because the fact is, at least in the now-old West, innovation moves at the speed of light while regulation moves at the speed of paper. In the current environment, light beats paper.

We live in the world we do. As humans, we innovate for advantage. To be sure, there are always disadvantages. While individual and cultural preferences and definitions vary, basic human flourishing consists of maximizing advantage and minimizing disadvantage. We currently don’t do a great job of that for the vast majority of people on Earth.

As I show in the following pages, Marshall McLuhan didn’t always believe we could do much about it. At one point he states that the forces at work are too great and complex to hope to be able to ‘predict and control.’ Crucially, he changed his mind after a period of intense study in the late 1950s. He had a certainty that through close study of the nature of human innovation we could be more deliberate about both the development of technology and the deployment of it in order to create environments which nurture the kinds of people and cultures we desire.

I’m not suggesting that this is simple or easy, but that it’s possible. I’d even suggest it’s necessary and overdue.

Despair is an anchor chained to our legs dragging us down, drowning us. It’s also optional. There are far more reasons to have hope than to be hopeless but it seems that it’s more difficult to notice the things which give us hope than the things which take it away. It certainly doesn’t help that our idea of ‘news’ is typically reporting what’s going wrong.

Hope is critical to our survival. If we don’t believe we can survive, it makes survival all but impossible. If we don’t believe that things can get better, what’s the point in working toward making it happen?

Because we are not helpless, we need not be hopeless.

— end of ‘Maelstrom Escape Strategies’ part one —

Marshall always stood for hope in my mind. I appreciate that you are keeping it alive, while simultaneously giving the devil of cynicism his due.

Lets go!!