Sleight of Mind: How Marshall McLuhan 'Read the Contemporary World.'

Often called a ‘prophet’ or a ‘guru,’ McLuhan was no magician—he was methodical. He insisted “I am always careful to only predict things which have already happened.' Here's how he did it.

‘He wasn’t ahead of his time, he was ahead of his contemporaries’, my dad said to me.

“We need new perceptions to cope. Our technologies are generations ahead of our thinking. If you even begin to think about these new technologies you appear as a poet because you are dealing with the present as the future. That is my technique.” ‘Encounter’ Magazine, 1967

He was adamant that he didn’t predict, but described what he sensed around him in the present. This, he said, was the unique gift of the artist. That they experience and express what is happening in the present and if it looks fantastic and foreign to us it’s because we’re stuck in the past or just that slow to catch on.

“The future is now. The teacher of the future is always the present, and it is very difficult to look at the present. Everything that is going to happen in 10 or 20 years is happening now, right under our noses.” ‘Education in the Electronic Age,’ 1967 speech

We are the sum of our senses.

It is the artist and the young, senses open and raw, who experience things first.

The generation gap is not one of time but of technology, of sense and sensibility. Like many of our devices, which have factory settings, we have faculty defaults, a kind of base setting (tolerances, thresholds) of our senses singly and together which go a long way to making us who we are, explaining why one kind of music is pleasing to one group of people and not another: media make sense.

Put very simply: as much as we’re born into an age, an environment, a generation, we are born of an age, a generation, an environment. We are shaped, fashioned, acclimatized.

I can hear the ‘the message is the message’ people with their war-cry of ‘Technological Determinism!’ Yes, we shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us—but this does not mean that we’re helpless or that we need be hopeless.

“Determinism is the result of the behaviour of those who are determined to ignore what is happening around them. Recognition of the psychic and social effects of technological change make it possible to neutralize the effects of innovation.” Letter to Life Magazine March 1, 1966

So how do we do that?

This, to me, is the big question, and it has a few parts, but I think the main obstacle is that there needs to be a critical mass of awareness before any change is possible:

How do we (humans, the world) come to a general understanding of the role which our media play in shaping is personally and socially – how do we get people to understand that ‘the medium is the message?’

That’s a tall order, and really what I am constantly chipping away at. It’s essentially why I created The McLuhan Institute in 2017.

PART TWO: getting back to where I started but got a little sidetracked or maybe not really.

Last week I gave a lecture at RMC. Located in nearby Kingston, Ontario, I had always thought of the Royal Military College as ‘Canada’s West Point.’ I was running a little late but luckily, and strangely, there was a strike happening and the strikers were blocking the entrance.

Picture a few dozen people protesting, signs aloft. Then someone is in a black and white cow costume. And there’s a loudspeaker pumping Usher like it was Superbowl Sunday. Oh, Canada.

I finally get in to the classroom and am confronted by rows of students in fatigues, and I made the inevitable clumsy joke about being tired, then launch in to my performance.

It’s not the first time I’ve been invited into a classroom to talk about McLuhan and media. Thankfully. It took me a while to get the hang of it. The trouble is that the McLuhan Galaxy is so vast, it’s hard to know where to begin, and it’s easy to overwhelm. I learned the hard way that by trying to accomplish too much, you easily accomplish very little, or even worse, turn people off completely.

Early in my ‘career,’ I was invited to guest lecture a class at Queen’s University (also in nearby Kingston, Ontario – TMI and I are an hour’s drive west in Prince Edward County). I was psyched. I make a few pages of notes. I would teach them all the things! Unfortunately, I was let’s say not very expert in everything I was going to say, but why let that stop me?

Well, I quickly got in over my head and when the questions came, I couldn’t answer them. What an awful feeling. I really blew it. But I learned a few very valuable lessons:

First, don’t pretend to know more than you do. It really is ok to not know everything.

Second: particularly with regard to this work, a little goes a long way. If you can manage to get across one valuable idea, that’s no small thing.

I was fortunate that the Queen’s prof gave me a second chance. (Shoutout to Roel). It had bothered me that I blew the opportunity. A few years later I got in touch and asked if I could have another shot at guest lecturing a class, and he kindly agreed. Instead of the ol’ ‘spray and pray’ scattergun approach I went into sniper mode. I led a workshop on ‘figure and ground’ where we focus on exploring the ground or ‘media environment’ surrounding a technology. Spending a class looking at the ‘environment of services and disservices’ surrounding something like the smartphone makes it easy to understand why it’s less the content or use than the medium or environment which is ‘the message’ or shaping force.

At RMC, I was invited to talk about Marshall McLuhan in relation to this English course titled ‘Reading the Contemporary World.’

I love a good title. You invite me to talk to a class taking a course called ‘reading the contemporary world’ and I’ve got a mandate to talk about how Marshall McLuhan read the contemporary world.

The first point to make regards ‘reading,’ which allowed me to speak for a few minutes about my favourite technology: words. There’s the word in the mind, the province of Dialectic, or Logic. There’s the spoken word, the province of Rhetoric. There’s also the written word, which is the province of Grammar. Grammar has two major parts, etymology or where words come from, and interpretation, what words mean; and, classically, deals with two main books: the bible (the ‘Word of God’) and the book of nature – the ‘writing on the wall.’ ‘Reading the Contemporary World’ brings to my mind first Grammar.

Another point is that Marshall McLuhan was an English prof and expert in modernist poetry whose side hustle was in examining and commenting on culture and technology, and that the two things were less accidental than one might imagine.

If anyone gives you side-eye for pursuing a degree in English literature, point them toward Marshall McLuhan because, in short, Marshall McLuhan took what he’d learned about literary criticism, applied it to culture and technology, and became one of the leading figures of the 20th century.

This brings me to two side points:

For one, when Marshall McLuhan first enrolled at the University of Manitoba, it wasn’t for English but for Mechanical Engineering. This is important because it shows his interest in structure, in the way things work. It also shows that he was technically inclined. This interest followed him to his study of literature then technology and culture as his abiding interest in most things was structure, or form, and effect.

I sometimes wonder ‘what if’ Marshall had stayed in Engineering, what he might have accomplished there. Would he have found his way into a similar realm of culture and technology but rather than on the criticism side, on the engineering side?

These ‘roads not taken’ fascinate me.

Growing up in Winnipeg, Marshall built a small sailboat and liked to spend time on the water. He thought himself a sailor until he and his friend Tom Easterbrook crossed the Atlantic to attend Cambridge. It was the height of the Great Depression, and Marshall had won a scholarship, had little else besides. He and Tom brought their bikes and had arranged to work their passage to England on a cattle boat. It is difficult to imagine a less pleasant way to cross an ocean. Marshall discovered he was not the sailor he thought he was.

So who was Marshall McLuhan? An English teacher? A sociologist? A Media Guru?

“I am not a ‘culture critic’ because I am not in any way interested in classifying cultural forms. I am a metaphysician, interested in the life of the forms and their surprising modalities.” —letter to Joe Keogh July 6, 1970

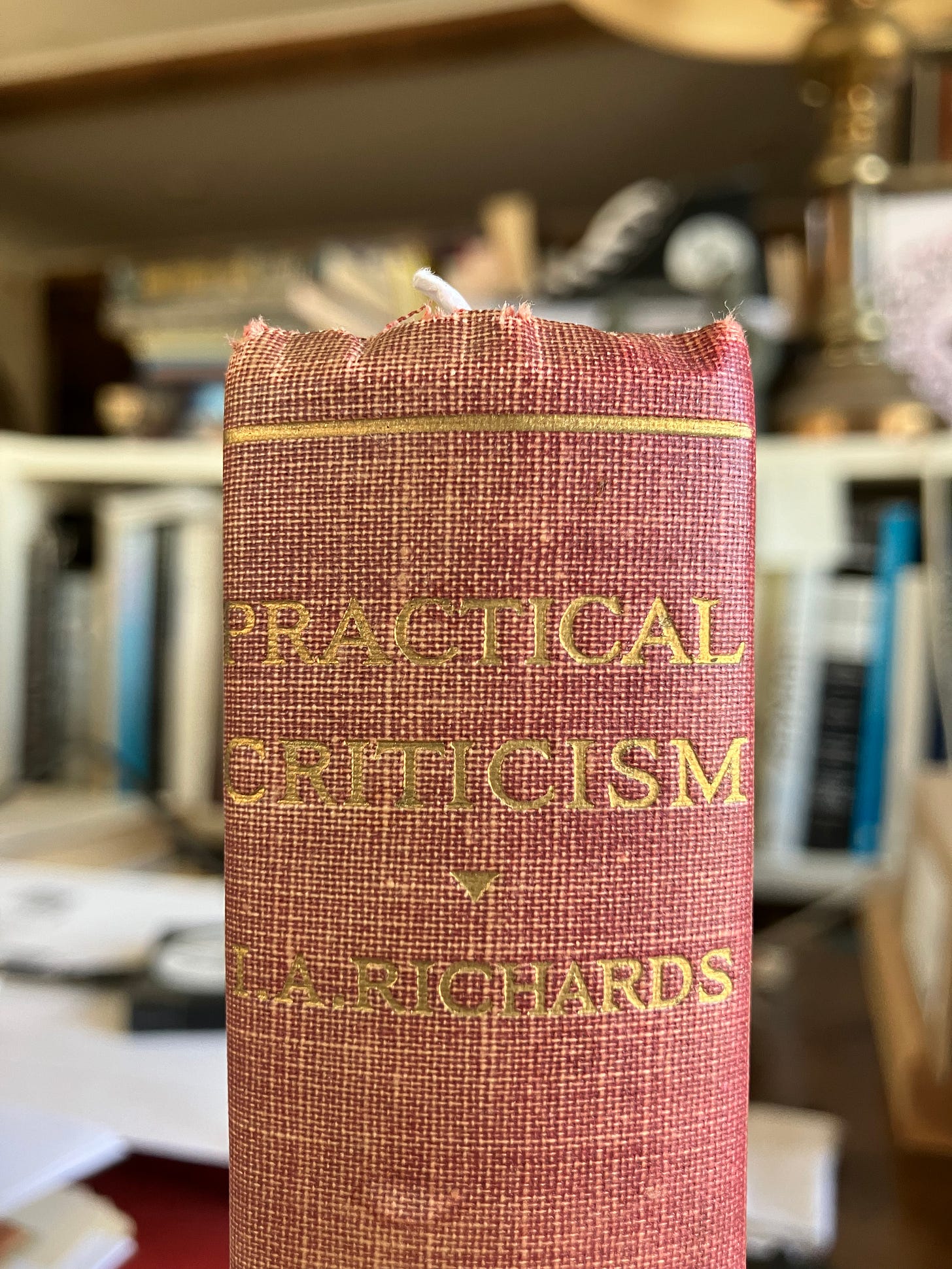

At Cambridge, Marshall studied under IA Richards and FR Leavis, founders of ‘Practical Criticism,’ known in North America as ‘The New Criticism.’

What was new about Practical Criticism was that it was concerned with effect, with discernment. Richards (and Leavis, among others) wanted to find out what made literature good or bad, so they assembled a group of poems from more or less well-regarded poets. For the well-known authors, they chose works which were lesser-known. The idea was that no one would be able to recognize the author and ‘cheat’ by judging a poem good or bad because the author was highly regarded or not. They distributed the poems to grad students and professional critics and asked them to judge the works and give their reasons.

A scandal ensued.

The scandal was that no one seemed to agree on which poems were good and why. The results were really mixed, and allowing for some variation, good literature should be good literature and the best minds of the day should agree. They didn’t.

This led Richards to develop (and publish) Practical Criticism, which sought to identify criteria with which to judge poetry and literature.

“The all-important fact for the study of literature—or any other mode of communication—is that there are several kinds of meaning. … Language—and pre-eminently language as it is used in poetry—has not one but several tasks to perform simultaneously, and we shall misconceive most of the difficulties of criticism unless we understand this point and take note of the differences between these functions. For our purposes here a division into four types of function, four kinds of meaning, will suffice.

“It is plain that most human utterances and nearly all articulate speech can be profitably regarded from four points of view. Four aspects can easily be distinguished. Let us call them Sense, Feeling, Tone, and Intention.” I.A. Richards, ‘Practical Criticism: A Study of Literary Judgement,’ 1929, pp180-181

Marshall wrote to a ‘Mr. Strappers’ in 1961:

“What is known as ‘the new criticism’ in North America I learned in England in 1934-36, at Cambridge. I simply extend this kind of ‘language of forms’ analysis from poetry to the popular media.”

In the forward to ‘The Interior Landscape: The Literary Criticism of Marshall McLuhan 1943-1962,’ Marshall writes:

“The effects of new media on our sensory lives are similar to the effects of new poetry. They change not our thoughts but the structure of our world.”

Eric McLuhan, Marshall’s eldest child and closest collaborator, my father, said:

“Practical Criticism gives you the tools for looking at the media. The moment you work the audience into the equation, and the effects on the audience into the equation, and the effect on, particularly, not the audience’s ideas but the audience’s sensibility, which is the big key in the arts: they’ll paint pictures of roses or write poems about pretty girls in Spring, but the thing that changes from one generation to another is the perceptions. So you can use the topics as an anchor, and see what’s changing in the context; and that’s the perceptions of the reader, or the audience – and there you are. That’s the big door, wide open, into media.”

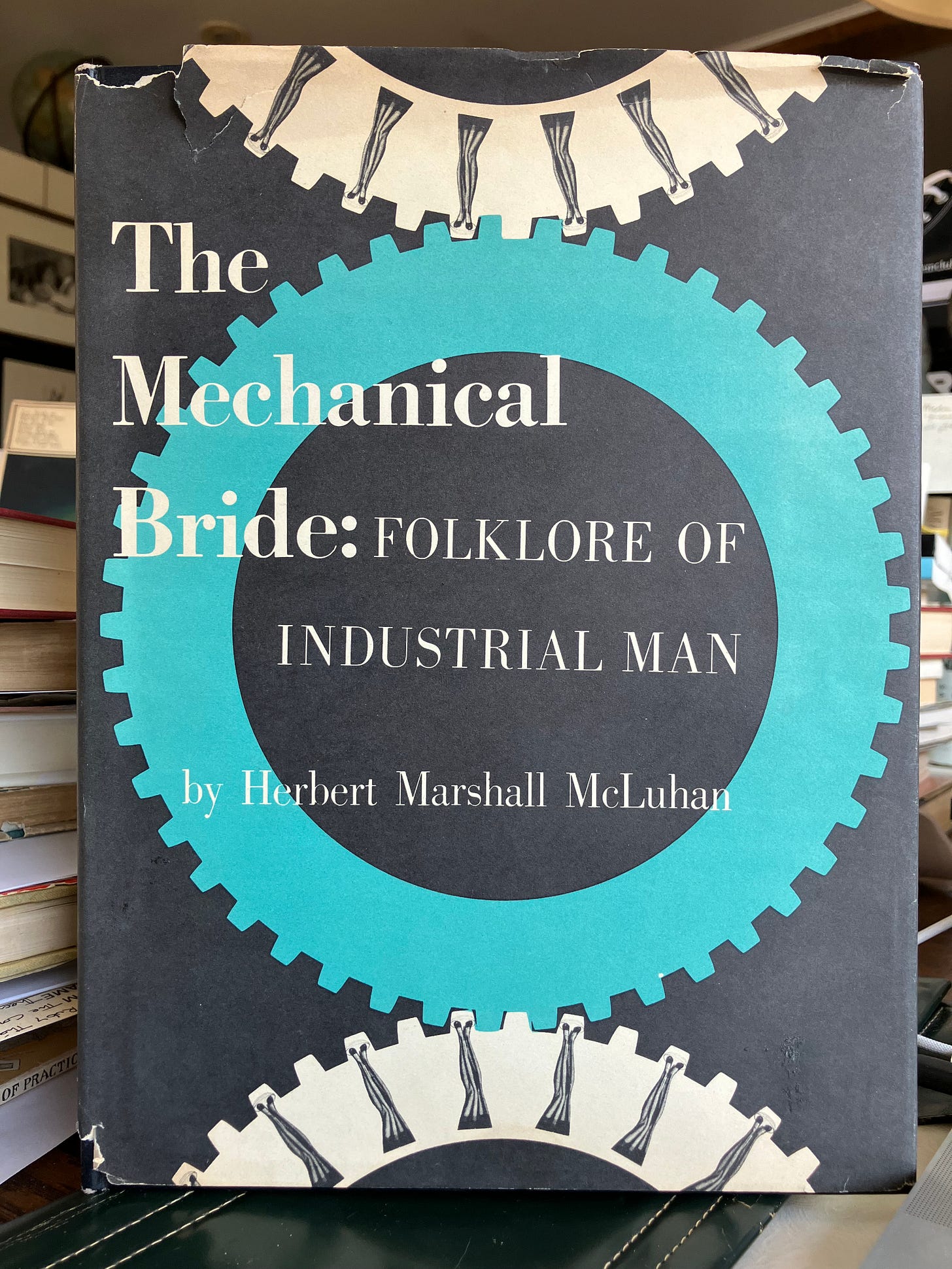

Back on this side of the Atlantic, Marshall got a teaching job in the US at the University of Wisconsin. Marshall had grown up in Winnipeg, had just spent several years at Cambridge University in England, and landed at Madison, Wisconsin. He was confronted with a group of people he didn’t understand and to try and get to know them he did something very unusual for the time – he looked at their popular culture, comics and advertising. He realized that these were forms which were reaching these students, and he might use them as a way in. This might not sound radical today but the better part of a century ago it was.

The material he developed in these classes would form his first book ‘The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man’ (Vanguard Press, 1951).

“This provocative book might well be termed 100,000,000 Guinea Pigs, for it reveals the insidious emotional appeals used by present-day advertisers, columnists, creators of comic strips, etc. In addition, it is an Arabian Nights entertainment of the mind which opens the door on a new world of popular culture and mythology.” —dust jacket, ‘The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man.’

“Ours is the first age in which many thousands of the best-trained individual minds have been made it a full-time business to get inside the collective public mind. To get inside in order to manipulate, exploit, control is the object now. And to generate heat not light is the intention. To keep everybody in the helpless state engendered by prolonged mental rutting is the effect of many ads and much entertainment alike.” —Preface, ‘The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man.’

This book is an outlier of McLuhan books. Many people prefer it to later works. Marshall takes a more direct and judgemental tone. It’s a lot of fun. It’s also closer to what’s considered ‘media literacy’ today than the main of his work which he considered an ecological approach. ‘Media literacy’ is almost completely directed toward content, whereas most McLuhan work begins with setting content to the side and examining the effect of the form, of the medium itself as an instrument and as an environment and the ‘personal and social consequences’ thereof.

This is not to dismiss content. Marshall was a writer and poetry lover. He loved content. But he realized that the ‘personal and social consequences’ of media come less from their content than their form. Our obsession with content blinds us to structural effects.

“Western man is an easy victim when he slips in to the habit of appraising media situations in terms of their ‘content’.” ‘Report on the Project in Understanding New Media’ 1960

Wisconsin was a short gig, followed by a few years at St. Louis University where Walter Ong was a student and colleague, and in 1946 Marshall McLuhan landed at St. Michael’s College, University of Toronto, where he would remain for the rest of his career. Here is where we see McLuhan expand from English Literature and Communications into Media Studies

McLuhan, along with anthropologist Edmund Carpenter, received a Ford Foundation grant to conduct an inter-disciplinary ‘Culture and Communication’ seminar, a product of which was the highly-regarded ‘Explorations’ journal (1953-1959), and the birth of ‘The Toronto School of Communication’ perhaps (if such a thing existed or is just a handy label for us today).

The advantage of relating this material in a class at RMC is that, being a military school, they’re very conscious of the time and its limits. I just talked for my allotted time, and the students (except for a couple who kept me in the hallway for a while) left. Here, I don’t seem to be running out of time or paper. But I’ve started, I’ll press on. You’re free to leave or stay or leave and return.

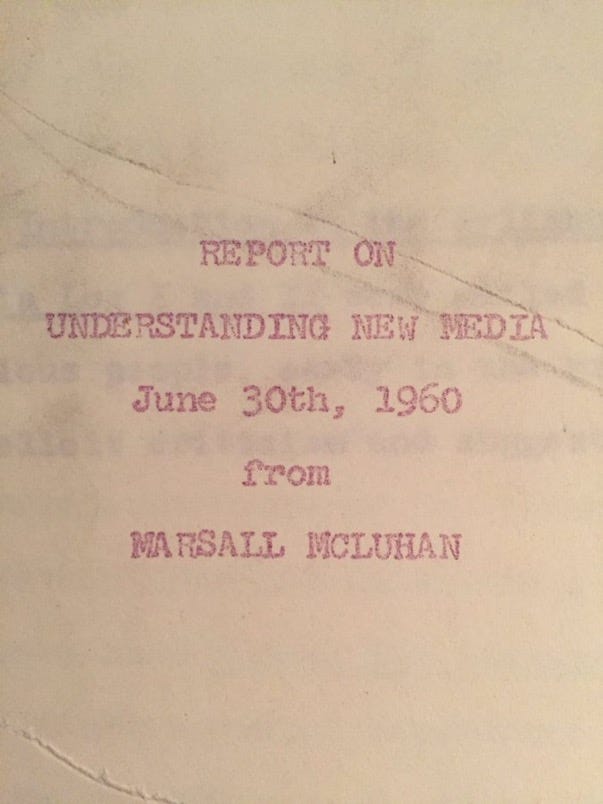

Marshall’s big breakthrough happened at the end of the 1950s when he was commissioned by the National Association of Educational Broadcasters and awarded ‘Project 69’ in Understanding New Media. He spent the better part of the next two years in detailed study of media, their structures and their effects, and his ‘Report on the Project in Understanding New Media’ was apparently to be a highschool curriculum and though Marshall seemed to think this was high-school level stuff, I don’t think anyone knew what to do with it. It’s a remarkable report, which begins like this:

“Report on Project in Understanding New Media

Prepared and published by the National Association of Educational Broadcasters, pursuant to a contract with the Office of Education, United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

Consultant: H. Marshall McLuhan

June 30, 1960

GENERAL INTRODUCTION TO THE LANGUAGES AND GRAMMARS OF THE MEDIA

Early in 1960 it dawned on me that the sensory impression proffered by a medium like movie or radio, was not the sensory effect obtained. Radio, for example, had an intense visual effect on listeners. But then there is the telephone which also proffers an auditory impression, but has no visual effect. In the same way television is watched but has a very different effect from movies. These observations led to a series of studies of the media, and to the discovery of basic laws concerning the sensory effects of various media. These will be found in this report.”

Here is a selection of quotes (not in chronological order) from the introduction to the report:

“The present report deals with the major media as languages in the full structural sense. That is, any medium based on any of our senses had the power of imposing its own assumptions.”

“We are obliged to learn the language of objects, and especially those object that are media. For they can pull the rug out from under your world or pop a new one under you while you are unawares.”

“The language and grammar of a medium have nothing to do with its content or programming.”

“The study of media constituents and contents can never reveal the dynamics of media effects.”

“It is the ratio among our senses which is disturbed by media technology. And any upset in our sense-ratios alters the matrix of thought and concept and value.”

“This is what I have meant all along by ‘the medium is the message’ for the medium determines the modes of perception and the matrix of assumptions within which objectives are set.”

“It is only by understanding the operation of media in the swift making and unmaking of cultures that we can hope to sustain the properties uniquely valuable in each medium.”

“Whenever man has suddenly attempted the translation of one kind of experience into another kind of experience, a human crisis has occurred.”

“It is only in our present century that we have had sufficient speed and simultaneity of access to large bodies of collective cultural data to enable us to understand the dynamics of change and cultural translation.”

“All of my recommendations, therefore, can be reduced to this one: study the modes of the media, in order to hoick all assumptions out of the subliminal, non-verbal realm for scrutiny and for prediction and control of human purpose.”

Each of those quotes is an essay. You could take them and apply them to AI. You could put them in front of Congress. Someone probably should. Imagine if Congress called Marshall McLuhan to the stand?

Anyway…

Marshall McLuhan then spent four years reworking and rewriting the report and turning into a more (less) conventional book. Although the NAEB report was never widely published (it really should be), the reworked material was published by McGraw-Hill in 1964 as ‘Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man.’

Except for a few bits thrown into the 2003 ‘critical edition’ of Understanding Media published by Gingko Press, the Report has never been published widely. It should be.

Here are a few tips for reading Understanding Media:

It helps to know that it began several years earlier as that 1960 report, and that it was deliberately reworked. You might ask why he did that. An expert in English Literature, he could have written it in any of the conventional styles but that wouldn’t have accomplished his object. He had an effect he wanted to achieve, an audience he wanted to reach. He had an extraordinary grasp of communication – he knew that learning happens on the reader’s side of the page, not the author’s. He also knew the limits of the form and that he had to hack it.

Approach it like the collection of poems that it is. Unlike more conventional fiction or non-fiction, the reader of poetry expects to do some work. At least half the job of ‘making sense’ is the reader’s duty to achieve. No one sits down to read a collection of poetry cover to cover in one sitting. In UMI, my extended Understanding Media course, we take it page by page; a paragraph, a sentence, sometimes a word at a time. Just like a poem that expands outward, each page is full of metaphor, references, which can be looked at more closely. Like poetry, UM is condensed and looking closer doesn’t dilute it but opens it up.

Understanding Media is essentially a guidebook to exploring the human effects of our technologies, and these effects are divided into two major groups: the personal or individual, and the social or group. Critically, it is not about content and interpretation but about forms and their structural effects as they meet and change our bodies, senses, minds, cultures.

It sits on a narrative structure, the transition between two major periods: the receding mechanical era, and its usurper, the new electric age.

It consists of two parts. Part One is seven chapters (McLuhan’s ‘Seven Liberal Arts’) which comprise seven methods or perspectives to use in looking at the nature and effect of any given technology. Part Two is twenty-six chapters (letters of the alphabet) which applies the methods from Part One against particular technologies from the spoken to the written word to radio to television and lastly to automation, with stops along the way.

It remains relevant today because while Part Two examines the past, Part One is timeless, useful to apply to any new human innovation.

These are just a few of the ways McLuhan ‘read the contemporary world.’ One thread among many, from his student days and Practical Criticism in the 1930s through to the Report, to Understanding Media in the 1960s. And this particular thread didn’t end there – it gets a reboot and plot twist in the early 1970s, but that’s a tale for another time.

The preceding is a text version of a speech given in an English class at the Royal Military College (Kingston, Ontario) last week. The title of the course is ‘Reading the Contemporary World,’ and being invited to address the class of military officers in training, I thought it a great opportunity to map out some of how Marshall McLuhan read the world. That speech was delivered from a single page of notes over about 30-40 minutes. The single page of notes was handwritten in about 15 minutes after a few weeks of back-burner thinking. This text was written (typed) on a MacBook over the last two days.

Thank you for your time and attention in this project and newsletter. I’m considering publishing the last year’s worth of Newsletter entries in a single bound volume. Is anyone interested in that?

I would be very interested in a printed bound volume of the collected newsletters.