Perception (n) versus Perception (v)

In this edition, we’re going explore some of the many senses of 'perception' and why, from the building blocks of experience to our opinions and beliefs, perception matters.

Dear reader: I should have had this out earlier but it’s an essay/exploration that kept growing and developing and it’s taken time to piece together, and even then it feels a bit rushed. I’ll try to get another post out asap to keep to my goal/pledge of one a month, and I appreciate your understanding that this is not published on a hard deadline or schedule but is more … humane. Thank you for your understanding and support!

idea: Public Relations is generally about public perception.

Steering, fixing, diverting, orienting perception. The label of 'public relations' is almost comically apt. This is one meaning of perception: an attitude, feeling, impression toward or of something. We talk about our perception of events, ourselves, or other people’s perception of same.

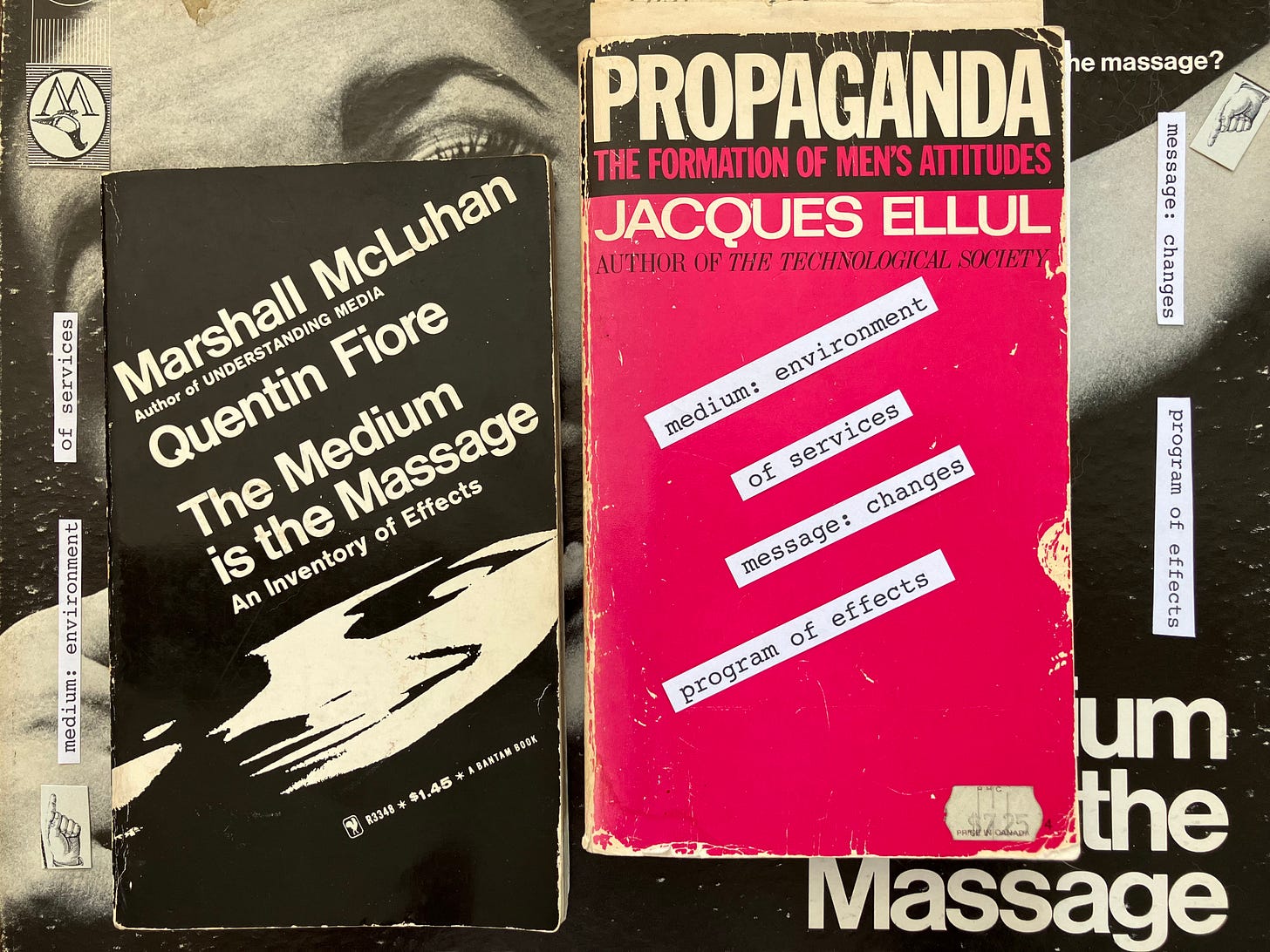

McLuhan work is, I think, primarily about perception. It's about the human senses and the human sensorium -- that is, about the nature and quality of our senses individually, one by one; and the nature and quality of all our individual senses together as a group (the 'sensorium'), it’s about the interface(s) between ourselves and the world. Clearly, ‘Communications’ or even ‘Media Studies’ and ‘Media Ecology’ are inadequate terms for what this work encompasses and entails. When you trace who we are back to how we are, you get back to the nature and quality of human senses, individually and collectively, the resulting perception or experience, and the meaning, attitudes, beliefs.

Here is the crux:

‘Perception’ here is about how we sense, how we receive information of any kind, before we classify that information or data, form opinions or feelings or judgements. Opinions, feelings, judgements are quite another type of perception. This sensory reception/perception precedes and shapes that (opinion, belief, judgement) perception.

All else is downstream from there.

We humans take a lot for granted. It’s one of our superpowers really. We compartmentalize so much of ourselves so that we can dedicate our attention to things which need it and let most things happen or exist in the background.

So you probably don’t think about the cycle of perception and how we receive and process information and, crucially, that a lot more happens in that process than we pay any attention to.

One way to think about the difference is to consider a glass of liquid in front of you. There’s how it exists before you observe it (what it looks like), pick it up (how it behaves, is it thick and syrupy, light and sparkly), and drink it (is it cold, effervescent, refreshing, awful?) Our answers to those questions depend on so many individual and cultural factors, but on each side of the questions and answers are these two different meanings of ‘perception.’

This get complicated, even paradoxical, and compounded by words with multiple meanings.

like ‘perception.’

or ‘medium.’

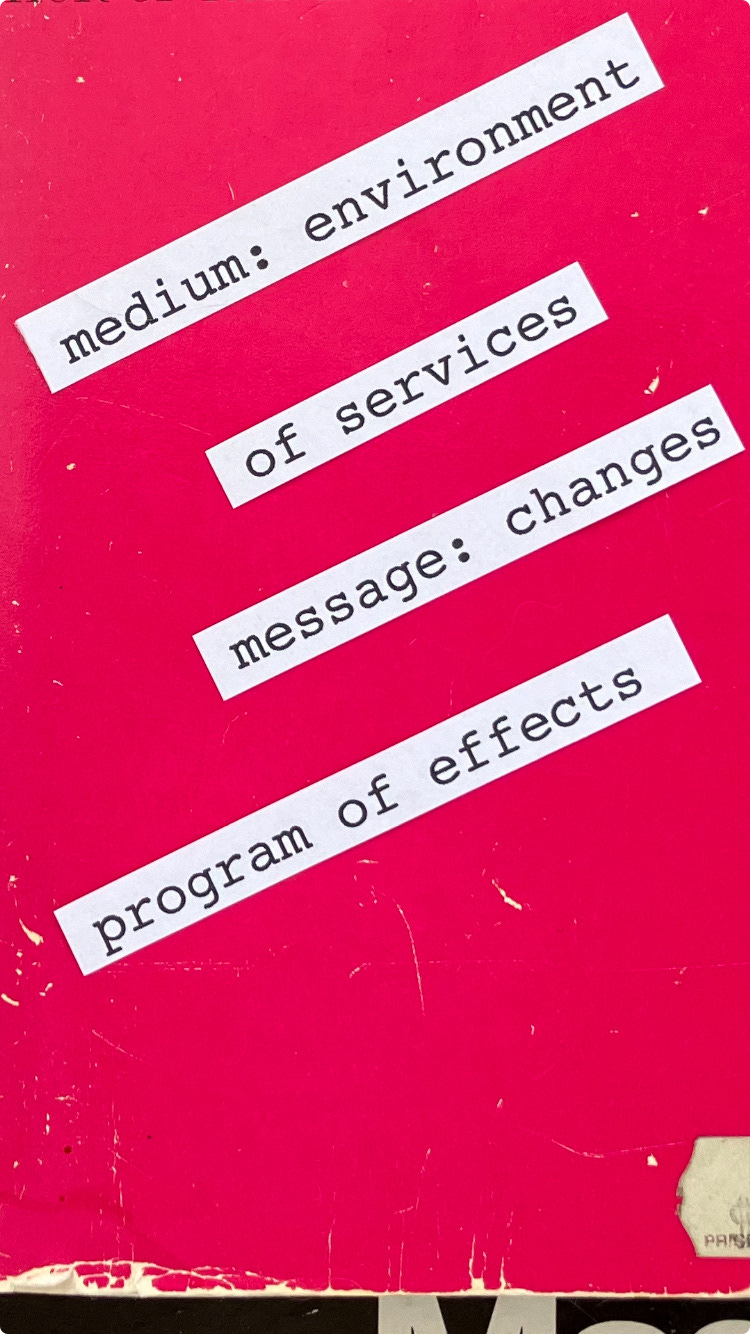

"The message of the media is always the changes they ring on the human senses and perception ... the medium or environment of services provides the message or program of effects."

(Marshall McLuhan, 1973 rewrite of 'the medium is the message' for an unpublished revision of ‘Understanding Media.’)

medium = environment of services

message = changes, program of effects

I say this a lot: we are the sum of our senses.

"This is what I have meant all along by 'the medium is the message,' for the medium determines the modes of perception and the matrix of assumptions within which all objectives are set." (McLuhan, NAEB report, 1960)

because

"The effects of technology do not occur at the level of opinions or concepts but alter sense ratios or patterns of perception steadily and without any resistance." (McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man,' 1964)

The whole of this essay is really an attempt at

spelling out that last sentence from Understanding Media.

“Here is another thought for you that is very controversial: I don’t see any point in making anything but controversial statements… I mean, you cannot get people thinking until you say something that really shocks them, dislocates them.”

(McLuhan, ‘Education in the Electronic Age,’ 1967)

/// Perception and Persuasion ///

We are persuaded most (and most easily) by what we perceive but are unaware of.

Because of the nature of our consciousness and attention, we receive a lot of information through our senses at any given moment which we don’t actively perceive, that is, bring up to the level of awareness or attention.

Persuasion deserves a few words in this discussion. It probably deserves a separate discussion. As with perception, there are a few different sides to persuasion. We might think of active and passive persuasion, where public relations engage in active persuasion, and media are all the more effective as they act beneath our notice – no less actively though they might seem passive.

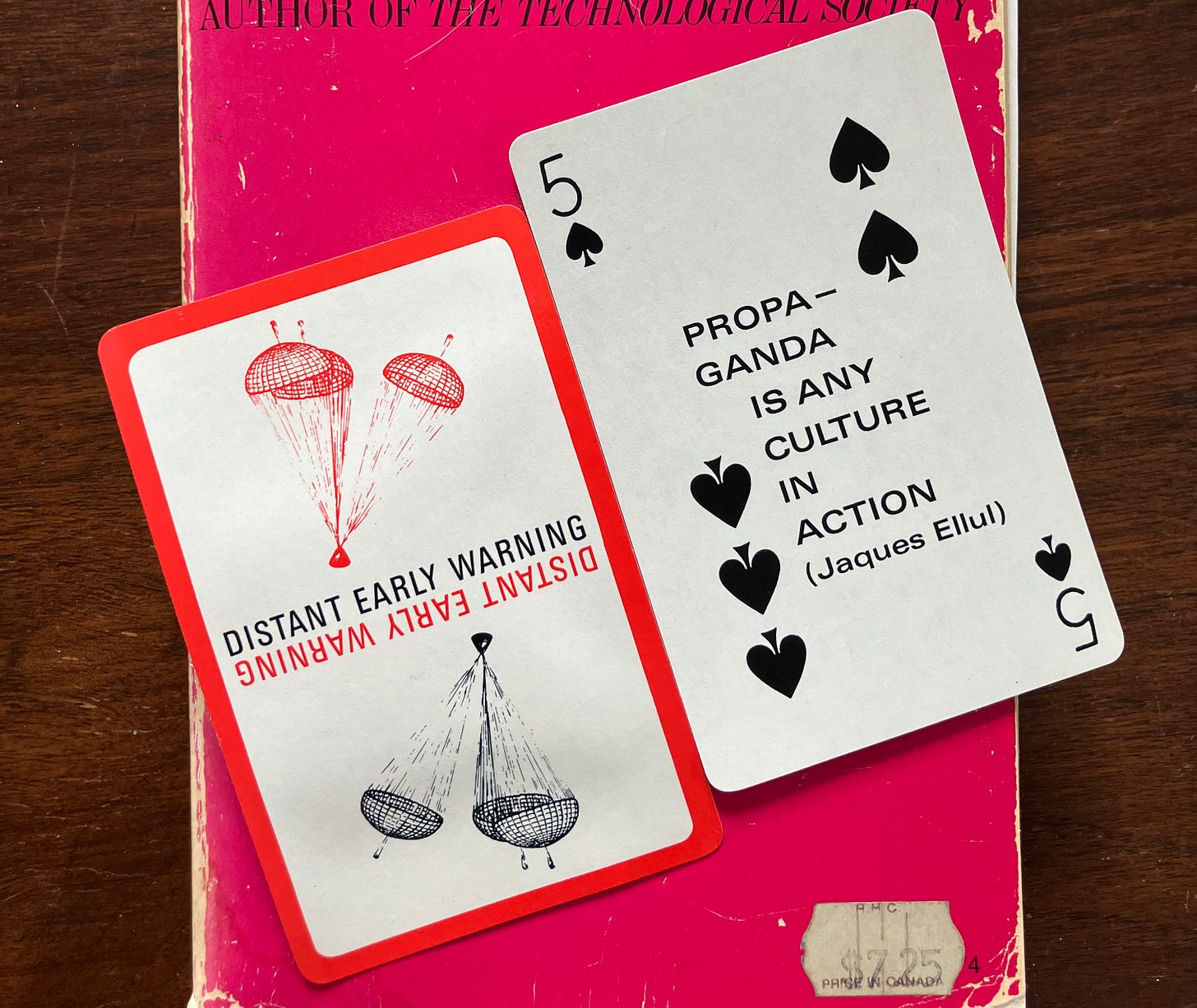

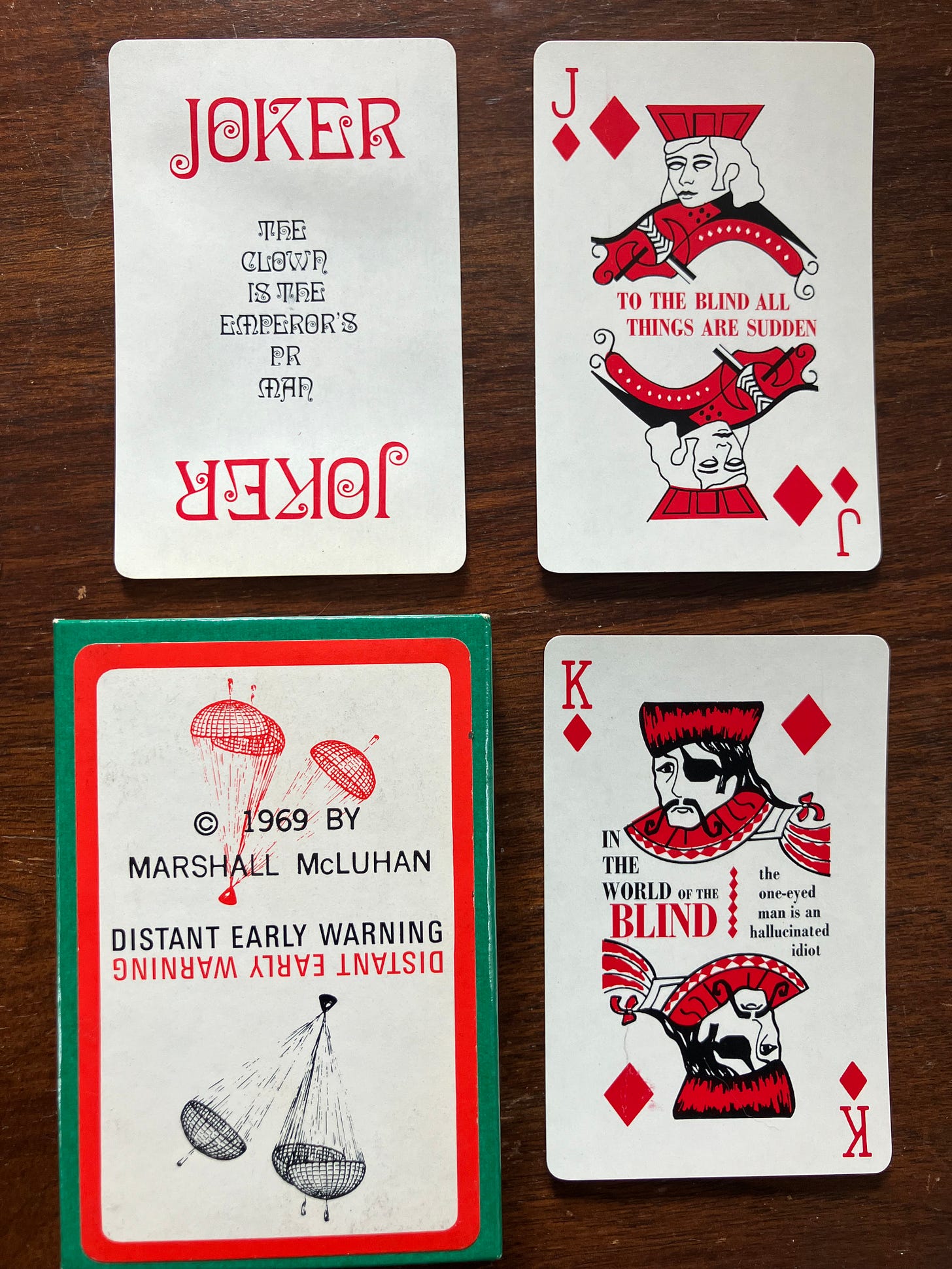

Marshall McLuhan seems to have been paraphrasing Jacques Ellul when he quotes him in his 1969 card deck that accompanied the first issue of the second (and final) year of his newsletter:

“Propaganda is any culture in action”

Sidebar: This essay would have been published at least a week earlier except for dropping in that Ellul quote/paraphrase. I went off in search of whether Ellul actually said “propaganda is any culture in action.” I thought I may have found the source when I discovered that Marshall McLuhan had written a review of Ellul’s 1965 ‘Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes’ What I discovered, instead of an answer, were many more questions.

This is a common pitfall around here: set off looking for one thing, find a dozen others.

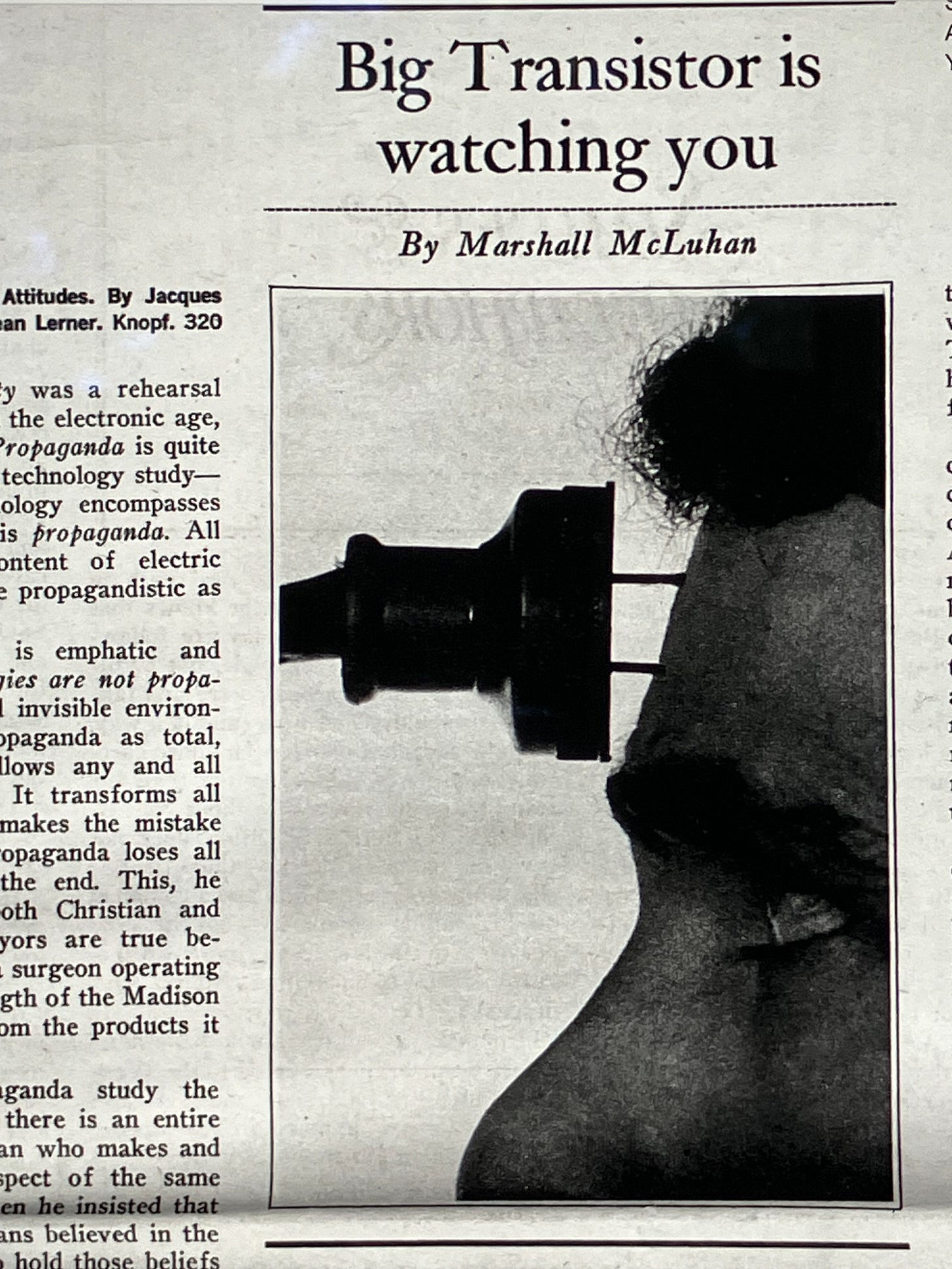

I discovered that Marshall McLuhan reviewed Ellul’s book in an article titled ‘Big Transistor is watching you.’ I discovered that I did not have a copy of it, though I had record of it. I further discovered that it was published in the New York Sunday Herald Tribune, November 27th, 1965 – a week after Tom Wolfe’s legendary profile of Marshall McLuhan appeared in the same publication. That profile, ‘Marshall McLuhan. Suppose he is what he sounds like: the greatest thinker since Newton, Darwin, Freud, Einstein and Pavlov—What If He Is Right?’ might be considered the snowball that turned into an avalanche as it heralded (sorry) several years’ worth of McLuhan in the public eye and ear.

I discovered that a copy of ‘Big Transistor’ was at the Kelly Library near McLuhan’s old office, and h/t to Simon for sending a copy to fill that hole in our archive.

“technology… conforms our sensory lives to new patterns and provides new outlook and motivation. In this respect technology has always been the master and never the servant of man.”

(Marshall McLuhan, ‘Big Transistor is watching you’, 1965)

Nothing persuades so completely as the things we take for granted: our culture, our language, our media.

The ideal aim with intentional persuasion (as in public relations or advertising or any other kind of sales) is perhaps to persuade in such a manner as the target of your persuasion is unaware of manipulation. The hard sell is the hardest sell. When someone wants or needs something, you don’t have to sell it so much as make it available. Why, you’re doing them a favour. So creating the want is as good as making the sale.

Often, we want what is pleasing to our senses.

Marshall McLuhan delighted in the alternate ‘the medium is the massage’ formula (supposedly, perhaps too conveniently, a printer’s error). A massage soothes, relaxes. It puts us at ease.

Again, a persistent problem when talking about 'perception' is that there are different meanings for the term. As with 'medium.' And 'message’. And ‘massage.’

We make many assumptions for the sake of convenience and efficiency. For our sanity, even.

People rarely pause to consider which definition is being used by an author or speaker, but instead automatically insert their own.

In the PR sense, when people talk about 'public perception' they are often talking about opinion. How people feel about a person, product, brand, idea, ideology, etc. It's a noun, a thing.

'Perception' as a verb, as an act, the main activity of our senses, is something else entirely. One’s ‘perception,' the noun, is something formed in the mind after 'perception' the verb has taken place in the senses.

"It is not easy to convince people that I am not dealing with ideas but perceptions, not concepts but observations. It is easy to disseminate ideas but it is difficult to train new perception." (Marshall McLuhan in the 'Financial Times of Canada,' September 11, 1972)

Side note: I don’t think many people have bothered to wonder about McLuhan’s statement here about ‘training perception,’ that he might have been up to something with everything he was doing in the public sphere for those years other than attracting attention for the sake of his ego. It’s interesting to note that he let the public eye drift away from himself without trying desperately to hold on to it. He, I believe, accomplished what he set out to do – at least, well enough to be satisfied and move on.

So: for the sake of this essay, I’m suggesting that

PR is about steering perception (noun)

Tech is about shaping perception (verb)

The main difference being, I think, that PR is about intentionally shaping public perception, while technologies shape and reshape our senses, shaping our perception and by immediate extension our very selves, as a 'side effect.' It's existential-level change which happens beneath our notice, and largely without intent on the part of the designers.

This is why when considering the effects of the form, content doesn’t much matter: because content is really the delivery mechanism for the changes which occur as a result of the impact of technology on us on a cognitive and sensory level, rippling out to have cultural and social changes.

Content is not the determining factor.

Because again, we are the sum of our senses, and even small changes have deep consequences. When you affect one sense, you affect all the senses because our senses work together as a 'sensorium.'

People get really upset about this. Maybe you’re getting upset right now. We should be a lot more upset about this than we currently are.

Maybe if we got a whole lot more upset about it we might do something about it.

This is most easily demonstrated by using the example of sighted vs non-sighted people. People with eyes to see have completely difference preferences and values (and experiences and lives and cultures) than those who don't.

It might sound simplistic, but hear me out: visual people value visual things.

In my home and office I am surrounded by a visually rich environment. Objects, art, clothing, photos. All these things add up to my personal experience, my identity, my culture, my memories, my history. My life, my work.

A blind person does not share these things. What do they care about the colour of their clothes or shoes - brands? Nike or Adidas, Prada or Polo, red or blue or black or white. Very different meaning for them. What do they care about the colour of their walls (or whether it's painted at all) or visual art?

See what I’m saying?

Many years ago my family had a house fire, and I was left with basically the clothes on my back. I had to go out and buy a whole new wardrobe, and it was slightly traumatic to discover that a large part of my identity had gone up in smoke, vanished, not to be recovered by a trip to the mall.

How much of our identities (that is, how we think of ourselves and how others think of us) are wrapped up in the clothing we wear - the colours, the brands. If you went to work tomorrow wearing something you wouldn’t normally, all black or all white, or a red top with green pants, how would that make you and those around you feel?

An argument can be made that visual art is one of the major pillars of our culture.

Without sight, what would we care about visual art? There would be few visual artists, little visual art. No galleries, no museums, no market. How would that effect the rest of our society?

I'm using this drastic example to show (demonstrate) how profoundly we are shaped by our senses: that

we are the sum of our senses.

Everything about us which we hold so dear, our tastes, our preferences, our values, are downstream of our senses, of perception. AND, each technology shapes our senses in different ways, shaping US in different ways.

This is why when we shape our tools, our tools shape us. Not the content, the medium.

This is why the medium, not the content, is the message. These are not content-level changes.

/// The only way to wake people up is to shake people up

Remember that 1967 quote about seeing no point in making anything but controversial statements? That the only way to wake people up is to shake people up?

“Going along with the total and, perhaps, motivated ignorance of man-made environments, is the failure of philosophers and psychologists in general to notice that our senses are not passive receptors of experiences.” (Marshall McLuhan, ‘Identity, Technology, War,’ 1970)

That ‘motivated ignorance piece deserves to be looked into further, but for the purposes of this essay, note that our senses are not static things. They change, and when they change, we change. We are the sum of our senses. Said another way,

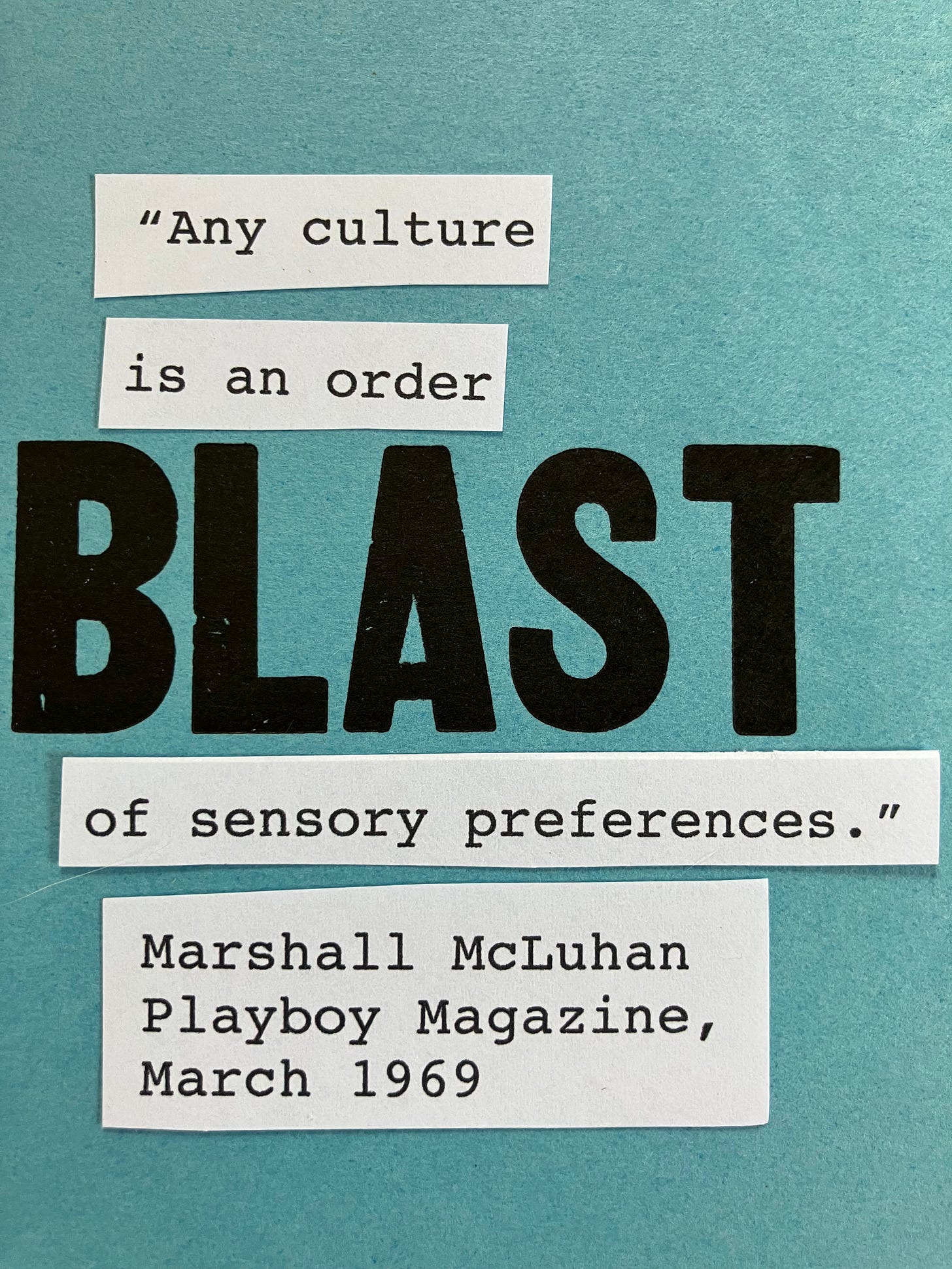

“Any culture is an order of sensory preferences.” (Marshall McLuhan interviewed in ‘Playboy’ magazine, 1969)

Our senses receive base settings (I think of it like our default factory settings) in the first few years of our lives. These settings, which Marshall McLuhan referred to as ‘thresholds’ in his remarkable 1965 essay ‘The Relation of Environment to Anti-Environment,’ are modified as we go along. It’s the first few years of exposure which set us up for life, but every bit of data, stimulus, information which passes through our senses shapes and reshapes them, and when you shape one sense you shape all our senses together (the sensorium).

If you suddenly lose your sense of sight, your entire life and experience forever changes: when you senses change, you change.

"If people are inclined to doubt whether the wheel or typography or plane could change our habits of sense perception, their doubts end with electric lighting. In this domain, the medium is the message, and when the light is out, there is a world of sense that disappears." ('Understanding Media', 1964)

Again, think of the blind person. A person who goes blind later in life will tell you about this way the senses work together because one of the dramatic things which happens is that your other senses react to the effect on any one of them. When you cut off the visual, your ears perk up, your sense of touch heightens, and so on.

Even for yourself, when you really want to concentrate on listening, what do you do? Close your eyes.

Even minor changes to the character, the quality of our senses, can have major implications to us individually and socially.

This understanding of the nature of our various senses and how they are formed and re-formed by our technologies is really the foundation of media studies from the McLuhan perspective, the base unit of understanding and operation from which everything else flows.

This is how when we shape our tools, thereafter our tools shape us.

This is why the medium is the message because

"...it is the medium that shapes and controls the scale and form of human association and action. The content or uses of such media are as diverse as they are ineffectual in shaping the form of human association. Indeed, it is only too typical that the "content" of any medium blinds us to the character of the medium." (Marshall McLuhan,'Understanding Media', 1964)

Despite what people like Marshall McLuhan have been trying to show and tell the world for a very long time, there is still a very low level of awareness about this.

We have yet to confront the role of technology in shaping our senses and our perception, or understand how deeply changes of this nature affect us. It goes to the core of our being, our identities and cultures

Media make and re-make our senses. An example of how blind we are to what this means is the term 'sensemaking.'

"Sensemaking is literally the act of making sense of an environment, achieved by organizing sense data until the environment “becomes sensible” or is understood well enough to enable reasonable decisions." (Atlantic Council 'Making sense of sensemaking' 2020)

This definition of ‘sensemaking’ is all about ‘making sense of’ and not about the senses at all. It’s about meaning, understanding.

Technology, on the other hand, creates an enveloping environment of stimulus/data/information which is received by our senses, altering them and us in the process, quite beneath our notice.

We only notice, after the fact, that our culture or way of life is no longer supported and are mystified (and upset to varying degrees) as to why that might be. We tend to respond with nostalgia or violence, fighting battles already lost rather than considering how to prevent future loss.

If you want to see an example of how broadly this idea in particular (or McLuhan in general) is misunderstood, go to Wikipedia. The only reason the entry for 'the medium is the message' has improved is that they have changed it over the years to be more vague:

"The medium is the message" is a phrase coined by the Canadian communication theorist Marshall McLuhan and the name of the first chapter in his Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, published in 1964. McLuhan proposes that a communication medium itself, not the messages it carries, should be the primary focus of study. He showed that artifacts such as media affect any society by their characteristics, or content.”

I’m sorry, what?

They end the entry with a dismissal of 'Understanding Media' as unoriginal:

"Many of the conceptions presented in this work are expansions, popularizations and applications of ideas initially conceived by Walter Benjamin and the dialog between his texts and other thinkers in the Frankfurt School in the 1930's and 1940's.”

The phrasing “he showed that artifacts such as media affect any society by their characteristics, or content” is (aside from being remarkably inaccurate) yet another affirmation of a reluctance verging on inability to think of media except in terms of its content. McLuhan treats as ‘media’ all human innovation. The subtitle of the book points to that: media are extensions of man. All extensions of man are media.

To use ‘man’ as a collective noun for humans is no longer acceptable, though it was once common. In another essay, Marshall changes the wording somewhat helpfully by referring to media as “extensions of human powers:”

“New Media, new technologies, new extensions of human powers, tend to be environmental. Tools, script, as much as wheel or photograph or Telstar, create a new environment, a new matrix for existing technologies.” (Marshall McLuhan, ‘New Media and the Arts,’ 1964)

To be sure, there is more to perception than meets the eye.

There’s a world of difference between our perception, or opinion, of events; and our perception, or experience of events. Both have much to do with who we are and how we perceive ourselves, each other, the world around us. But perhaps the simplest way to distinguish them is by considering how both PR and media change our minds.

I don’t want to close this without at least a hint of what to do about this.

As a last word on this exploration, and perhaps a first word on another:

“New art is the survival chart for relevance amidst the technological changes that distort and junk our existing sensory patterns.”

Marshall McLuhan article, unpublished, on Louis Mumford dated February 28, 1973.

Thank you for reading. As I said in the opening, apologies that it took a while to get this out. Starting with the notion of ‘perception’ as a verb versus as a noun, his has been a beast of a project which kept growing and eventually I just had to stop.

I appreciate your attention and support of my efforts.

I’m on the road for work over the next month but will publish again soon.

Jacques Ellul argues that propaganda does not primarily aim to change opinion, but to bring about "the active or passive participation" of a mass of individuals who are "psychologically unified through psychological manipulations."

The propagandist addresses the individual who is alone in the mass. Isolation in the mass "is a natural product of present-day society and is both used and deepened by the mass media...the listener to a radio broadcast, though actually alone, is nevertheless part of a large group and he is aware of it."

Propaganda uses the power of the mass media to reach the whole crowd at once, and yet addresses each individual in the crowd. In reality, propaganda only pretends to address the individual who is reduced to an average. Propaganda acts on what the individual has in common with others.

I absolutely love the integration of DEW cards here. More please!