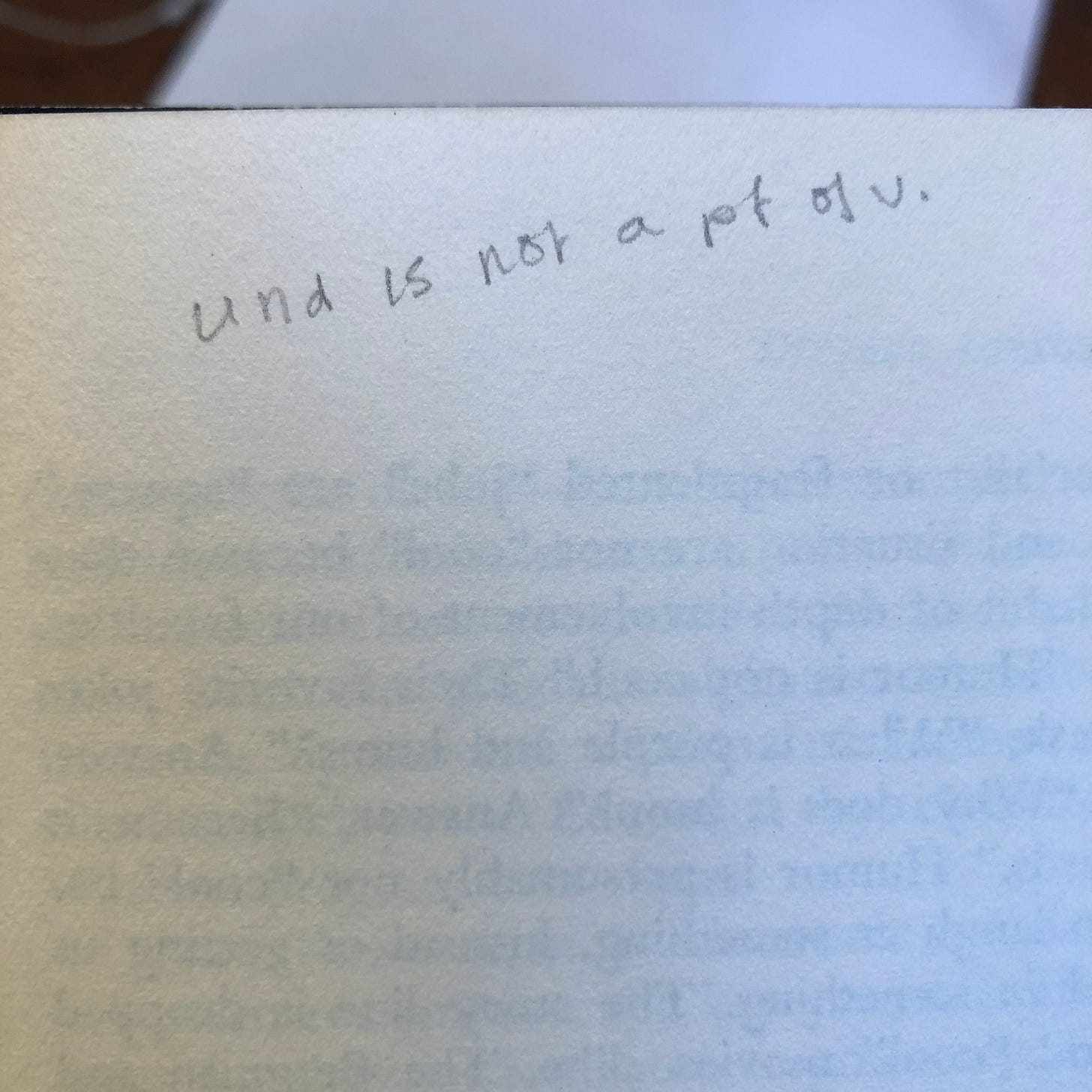

Understanding is Not a Point of View

maybe, it's the point of you.

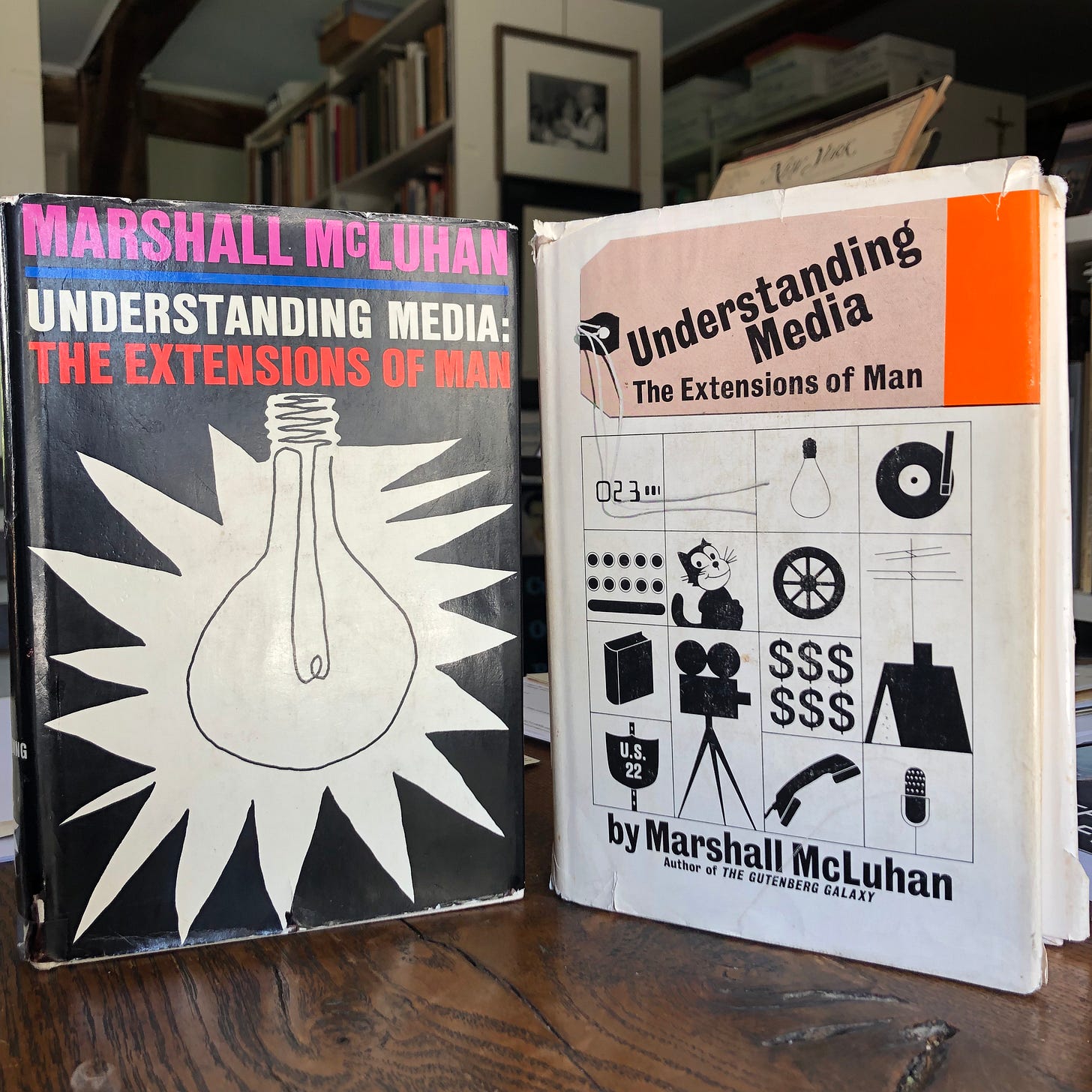

In 1972, following the success of ‘Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man’ (Marshall McLuhan, 1964) publishers McGraw-Hill approached Marshall about doing a tenth anniversary edition. The idea was to write a new preface, maybe add a few chapters to reflect the major developments and changes in the media landscape in the decade since the release of the book.

Was that good enough for Marshall McLuhan? In a word, no.

Marshall saw this an opportunity to address a major criticism of the book, namely that it ‘wasn’t scientific.’ Marshall, drawing on the history of science, disagreed. Actually, his methods were quite scientific – but of an older science than our modern one. Still, the question was that magic balance of equal parts annoying and interesting to put him to work. Them, actually.

At this point, Marshall’s eldest son Eric McLuhan had been working with his father for several years. It’s hard to imagine a closer working relationship than between father and son dedicated to the same pursuit.

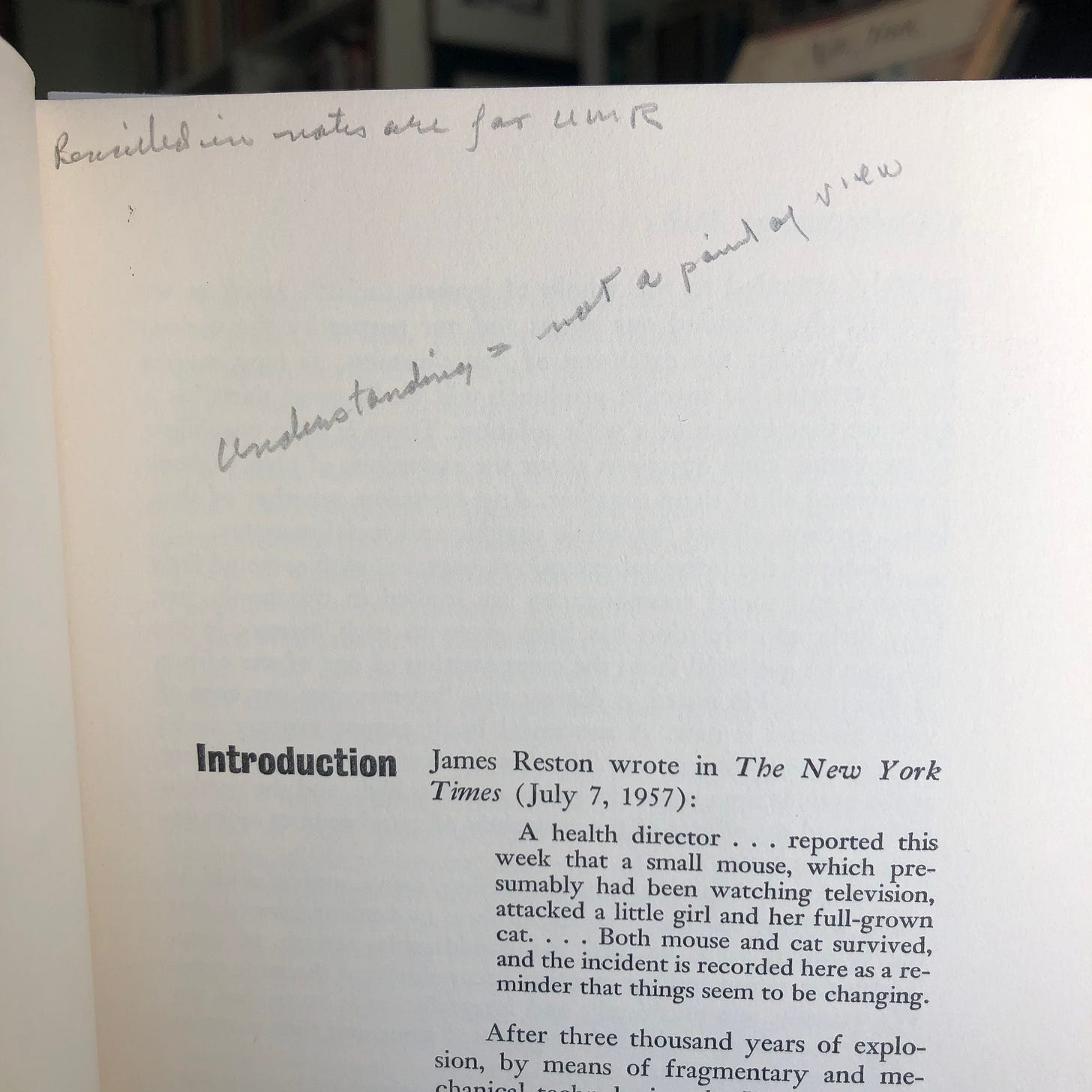

In modern science, there are Laws of Thermodynamics, Laws of Physics, of Gravity. These are ‘Laws’ because they are testable, universal, constant. Father and son together set out to determine whether there are properties of media which can be described as such. They informally called this project UMR, or ‘Understanding Media, Revised’ though the results were eventually published in 1988 as ‘Laws of Media: The New Science,’ the subtitle a nod to the work of Francis Bacon (Novum Organum) and Giambattista Vico (Scienza Nuova). The key here is to judge the McLuhan science less against moderns such as Einstein or Bohr, but more with Bacon and Vico. To discard your own point of view and engage with an open mind. Or maybe even to consider them all together and try to find some common sense.

The first thing was to each get a copy of Understanding Media, then go through it together searching for laws, for things which can be said about all technologies. A single exception, and you don’t have a Law.

Marshall ‘borrowed’ the first edition he’d given and lovingly inscribed to his wife Corinne for his use. Eric, the second printing with the cover designed by Howard Gossage and Margaret Larson (that’s a whole other story).

Both began making notes with the same sentence, and I can hear Marshall’s voice saying:

“Now Eric, at the beginning, let’s write ‘understanding is not a point of view.’”

Why is this interesting?

I teach a course called ‘Understanding Media Intensive’ where I lead students through the book page by page, word by word, tracking down references and exploring context and meaning and contemporary relevance. In all, it’s 36 classes about 2-3 hours each. It’s a lot. But the book is a lot. It’s not like any other book. It has more in common with an anthology of poetry than it does a textbook or conventional media studies tome.

It is not a single approach to studying technology and its ‘personal and social consequences.’ This is part of what people of the time (and since) have difficulty with. We tend to like single servings. Each of the chapters of Part One (seven chapters, a nod to the seven liberal arts, the ‘trivium and quadrivium’ of classical education) is a different approach. In Part Two of the book (twenty-six chapters, a nod to, you guessed it, the alphabet) the methods from Part One are applied to specific technologies in a most unconventional way. One could argue that this is where communication(s) studies became media studies by an enlargement of the category. Marshall considers as media not just conventional communications technologies like speech, printing press, telephone; but other products of human innovation such as clothing, housing, games. These, he suggests, are no less impactful. Indeed they have the same power to ‘affect the whole psychic and social complex.’

To understand these things, their nature and their effects – to Understand Media – a single ‘point of view’ is inadequate. One needs to come at it from all sides, from as many viewpoints as possible and using all senses, perceptive faculties, and fields of study: from communications, from literature, from economics, from anthropology, and from the arts as well as the sciences.

It is this approach, or this array of approaches, which makes the book timeless, as useful today as it was then and will be tomorrow. It is remarkable. Leading the dozen or so current students through this work over the last months as Midjourney, Chat GPT and the host of generative AI have come online, it seems as if the book were written specifically to help us understand them and our changing selves and work.

I’ve come to realize that it’s not accidental, but intentional.

It took me many years to make sense of the book. As a teen, a young adult, I didn’t get much from it. Now, every time I dive into it, I get more. It’s taken no small amount of mental maturity to get to a place where I can make headway. It’s also a matter of approach. I’ve found the book invites a different kind of reading than one might assume, a kind that maybe many aren’t prepared to engage in. If you approach it like a poetry anthology, you’ll get a lot further. You wouldn’t try to read a poetry anthology cover to cover in a sitting. You take your time. You sip, savour, explore, digest.

Allow me to suggest that if you’ve never read it, now’s the time. And, if you haven’t read it lately — now’s the time.

I can confidently guarantee that if you take the time to encounter this work on its own terms, it will change the way you look at everything around you, how it got to be this way, and where we’re headed.

The medium is the message.

Additional Notes:

These two copies of Understanding Media are a treasure trove, filled with Marshall and Eric McLuhan’s ideas, notes, observations on their work. If you happen to be in the Prince Edward County, Ontario, area some time, book a visit to The McLuhan Institute.

This instalment of The McLuhan Newsletter was inspired by the excellent and stimulating work of Noah Brier and company and their daily provocation ‘why is this interesting.’ Do yourself a favour and sign up to gain more points of view.

“A point of view can be a dangerous luxury when substituted for insight and understanding.”

Great article Andrew!! BBC Radio 4 broadcasted a nice piece on Gossage last week: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m001m4dk?partner=uk.co.bbc&origin=share-mobile